This article is re-posted from the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University.

At the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard, we have been advocating more systematic measurement of well-being to better assess what is going well and what isn’t, how things are changing over time, who needs help, and in what ways.

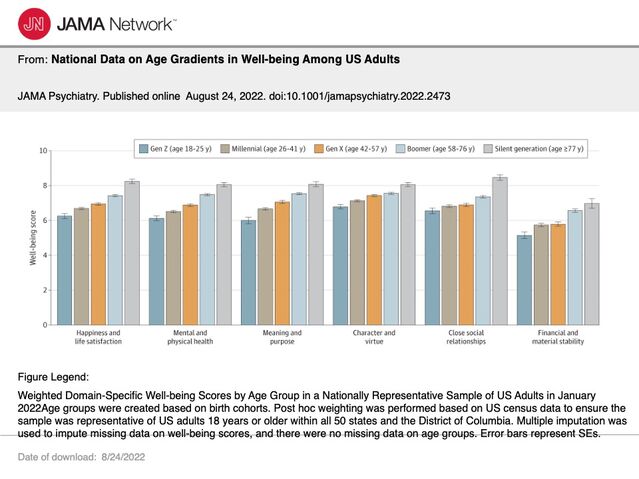

For the last couple of years, we have been reporting on nationally representative data within the United States on our flourishing assessment, covering numerous aspects of well-being, including happiness, health, meaning, character, social relationships, and financial stability. In a report we recently published in JAMA Psychiatry, we presented such flourishing assessment data for January 2022.

Some signs are encouraging, and for some age groups, the self-reported scores are roughly similar to the national averages we’d reported before the pandemic. However, one particularly striking feature of this most recent data is that young adults (especially those aged 18-25 years) are not doing especially well, and they are not doing well across multiple aspects of well-being.

Age and Well-Being

The traditionally reported patterns of well-being and age have focused mostly on happiness and life satisfaction. These had suggested that the relationship between well-being and age was U-shaped, with younger people and older people generally doing better than those who are middle-aged. Many of those who were middle-aged were perhaps struggling both with young children and aging parents. However, over the past decade or so, the shape of this pattern of well-being with age changed in dramatic ways.

In January 2022, the data indicate that, across the various dimensions of well-being, self-reported well-being scores strictly increase with age (see the figure below). This is true for happiness, but also for health, meaning, character, social relationships, and financial stability. The left part of the “U” has essentially completely flattened.

Relatively speaking, young people are not doing as well as they once were. They report being less happy and less healthy; having less meaning, greater struggles with character, and poorer relationships; and less financially stable compared to their older counterparts. The differences in well-being with age were, in fact, much larger than they were for gender or for race. There has been discussion of a national mental health crisis among youth. The present disconcerting data indicate that the crisis is much broader, embracing numerous aspects of flourishing, and with potentially dire implications for the future of our nation.

-

Source: Jama Psychiatry/Creative Commons

Speculations Concerning Causes

Data of the type we collected cannot tell us what is causing this well-being crisis. To try to tease apart causes, we generally need longitudinal data on the same group of individuals over time (as in our Global Flourishing Study). However, other data and studies might help give clues as to some of what might be occurring.

Some of the difficulty may well be economic: With housing costs ever increasing, inflation high, and substantial education debt, it may seem difficult for young adults to have hope for a more stable future.

Some of the issue may also pertain to a crisis in meaning. While universities have supplied increasing knowledge, it is not clear that they have done as good a job at providing comprehensive systems of meaning and understanding. Religions and philosophies have traditionally often supplied these, but participation in religious communities has declined substantially, especially among youth, which may also alter numerous other aspects of well-being. Crises in identity, including what seems to be a push in some places to have children wrestle with questions of their own gender identity even (as I have experienced in exploring educational options for my own children) as early as kindergarten, also may not help.

Geopolitical events and concerns ranging from the COVID-19 pandemic itself, to global warming, to threats of and realities of war, all also threaten well-being but may do so especially for those who have not lived much of life in more stable times. These issues are, of course, a concern in and of themselves, but a loss of frameworks of meaning may also exacerbate things.

Some of the well-being troubles may also arise from technology and social media use. The effects of social media use on well-being do, perhaps, vary somewhat by mode of engagement. However, some of the best studies suggest that, at least on average, and especially for high rates of use, the effect of social media engagement on well-being is negative, and social media use is considerably higher among young people.

A large part of the pattern we see with lower well-being among younger people might also have to do with disproportionate social effects of the pandemic on relationships across age groups. Those who are older, who have had established relationships and longer-term community, have perhaps been able to better weather the pandemic conditions over the past couple of years. Those with existing relationships and communities can draw upon those resources and have been able to more easily re-engage as pandemic conditions have lightened. However, younger people often do not have these pre-existing relationships and communities—indeed it is this stage in life in which relationships and communities are formed, and opportunities for such formation have been very severely impeded these past two years.

Political polarization may well be another cause. Such polarization has created hate and animosity, likely exacerbated by social media use, even to the point that political adversaries substantially misconceive the actual views of the other side. There seems less of an orientation to the common good. Weakening communities may also yet further be weakening a sense of the common good. A hateful, dysfunctional politics does not give rise to hope.

Moreover, a proper orientation toward the common good should concern not only present circumstances, across both sides of the aisle, but also a common good oriented toward the future, toward economic and social policies that enable young people to advance, that help young people flourish, and that will sustain society for generations to come. It is not clear at present that we have this.

The Way Forward

Our data, unfortunately, do not provide solutions, but the data do make clear that there is a problem that needs to be addressed. Data of the type we have presented also do not tell us whether the patterns of age and well-being have altered so that, under the current societal structures, young people will eventually improve with age (what would be called an “age effect”) or, alternatively, if, given what has occurred and the experiences that have taken place, the current generation of young people will continue to struggle (what would be called a “cohort effect”). Some of this may depend on the actions that are taken in the years ahead. However, regardless of which of these two explanations, or some combination of the two, is correct, the crisis at present seems clear.

We need to work on helping young people, of this generation and of subsequent generations, to thrive. We need to foster systems of meaning and deeper engagement with the most fundamental questions of life. We need greater discipline in our social media use, from individuals to communities to corporations. Parents and schools could appropriately restrict use and also help teenagers and others to develop healthier patterns of use; corporations need to take well-being studies seriously, and design platforms that do not impede well-being. We need to focus on rebuilding relationships and communities post-pandemic.

Finally, we need a politics more oriented toward the common good—both oriented toward the common good of the present but also toward the common good of the future, and of future generations. The well-being of our youth, and the future of our society, depend upon it.

References

Chen, Y., Cowden, R.G., Fulks, J., Plake, J.K., and VanderWeele, T.J. National data on age gradients in wellbeing among U.S. adults. JAMA Psychiatry, in press. Published online August 24, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2473