About one in five Americans identify as “Spiritual but not Religious,” or as I will say simply Spiritual. The Spiritual share many beliefs with religious people: most believe, for example, that “people have a soul or spirit in addition to their physical behavior” and that “there is something spiritual beyond the natural world, even if we cannot see it.” Their activities, however, are much more secular: they tend not to pray or to attend services. Those who are Spiritual think and feel spiritually, we might say, but they act secularly.

The Spiritual approach is an appealing perspective in a fraught world. On the one hand, many find that austere scientism from contemporary atheists lacks consolation or depth. On the other, the conventions and credos of organized religions feel constraining or simplistic to many, not to mention the abuses and political stances that have driven many away from long-standing religious communities. Given the bleak landscape of traditional institutions, the draw of the Spiritual is easy to understand.

There also seems to be a more practical case for being Spiritual. Many psychological or self-help movements make free use of spiritual ideas, divorced from the particular religions in which those ideas developed. This is true, for example, of the Human Potential Movement and such other movements that flourished in the 1960’s. But it is also true, in a deep way, of longstanding programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (which involves an appeal to a non-religious Higher Power), as well as contemporary therapeutic approaches such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (which draws freely on mindfulness techniques having their origin in non-Western religions). The core idea animating these approaches seems to be that a spiritual life, independent of any religious commitment, can be a touchstone to mental health.

But this idea itself rests on an empirical claim, not a spiritual one. The pragmatist approach to spirituality that runs from William James through contemporary psychotherapy—that the spiritual is useful, whether or not it is true—makes a specific claim about the effects of the Spiritual perspective. And here there are considerable grounds for skepticism.

Some of these reasons come from large-scale population studies. One UK study finds that people who are Spiritual possess higher rates of neuroticism and anxiety than do either people who are religious or people who are secular. An American study finds that Spiritual individuals have lower emotional stability and life satisfaction than do those who simply identify as atheist. These kinds of results are found in developing countries as well. A study in Brazil found that, among other things, Spiritual individuals have higher anxiety than people who are religious or those who are secular; indeed, being religious in the absence of spiritual beliefs was found to predict better outcomes than being Spiritual.

These population-level results are echoed in more specific findings and interventions. For example, there is a well-established relationship between religiosity and low criminality. One particularly discouraging study asked whether this also held for those who identified as Spiritual. They found just the opposite: individuals identifying as Spiritual were more likely to commit violent crimes than people who are religious, and more likely to commit property crimes than people who are religious and than people who are secular. This is a perplexing, and troubling, result.

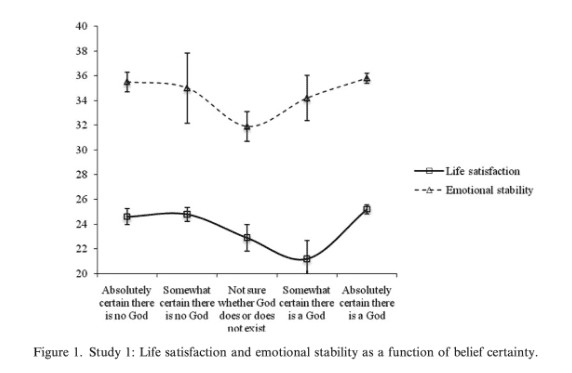

These kinds of findings are especially striking when displayed visually. The following graph from one prominent study of mental well-being and religiosity illustrates the relationship between life satisfaction and emotional stability on the one hand and certainty in God’s existence on the other:

Atheists and confident theists are best off, but those who are more ambivalent about God’s existence—an attitude that is associated with, though not exactly the same as being Spiritual—experience a notable dip.

All these findings, it bears emphasizing, are correlational. They tell us that there is some relationship between being Spiritual and certain outcomes—including criminality, emotional instability, and anxiety—but they do not tell us why these relationships exist. Specifically, they do not give us any information about whether Spirituality causes these outcomes. And it is in the nature of belief that these causal relationships are bound to remain somewhat inscrutable. We cannot randomly assign some people to be Spiritual, and some to be traditionally religious, and see what happens.

But, even without making claims about the grounds of these correlations, we face a certain puzzle. As noted at the outset, the thought that Spirituality is associated with psychological well-being runs deep in the therapeutic tradition. And this association is no accident. The individual practices associated with Spirituality have demonstrably positive effects on mental health. In fact, numerous studies have shown meditation practices to be effective in promoting emotional stability and strength in relationships. And Spiritual individuals, at least in the United States, are more likely to meditate than any other group, with nearly half meditating a few times a month.

But, considered as a group, these same individuals tend to have worse health, on balance, than people who are not Spiritual. This is not precisely a contradiction, but it is a deep tension. If particular spiritual practices are associated with good mental health, why is Spirituality itself associated with poor mental health?

This question, and the puzzle on which it rests, challenges a presupposition of the entire project of developing psychological interventions on the basis of religious practices. The presupposition is that one may, as it were, “pick and choose.” We can have the benefits of meditation without, for example, the orthodoxies of Theravada Buddhism, or the benefits of a Higher Power without the mainline Protestantism that was common among the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous.

This presupposition, what we might call the separability of the spiritual, is an appealing one, for religion seems to many to be a mix of mentally healthy practices, on the one hand, and objectionable requirements on action and thought, on the other. But reflection on the plight of the Spiritual gives us some reason to wonder whether spiritual practices are indeed always as separable as we might like for them to be.

John T. Meier is a psychotherapist in private practice and an adjunct faculty member at Lesley University. He is the author of The Disabled Will and Options and Agency. His current work revolves around understanding core topics in psychology – such as addiction, therapy, and mental health – from a broadly philosophical perspective.