This year marks the 80th anniversary of the birth of existentialism in France. Indeed, it would never have been born had France not known war and defeat by Nazi Germany. Those who had resisted under the occupation were not content to return to the way things had been. Heaved into a world shadowed by the human ashes over Auschwitz and mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they instead called for a revolution—one that was not just political, but also philosophical. They sought a new system of values to replace those that, in their eyes, had failed to prevent, perhaps even enabled, the unprecedented destruction wrought by dark ideologies and new technologies.

This urgency was most keenly felt by the young. Mais oui, these were the very same youths who donned black turtlenecks and baggy sweaters, slouched in basement jazz clubs and smoke-filled cafés. Perhaps you have already heard this tune, quite literally, in the musical “Funny Face,” when a bookish young woman, played by Audrey Hepburn, finds herself in Paris and declares “I want to see the den of thinking men like Jean-Paul Sartre/I must philosophize with all the guys around Montmartre and Montparnasse.”

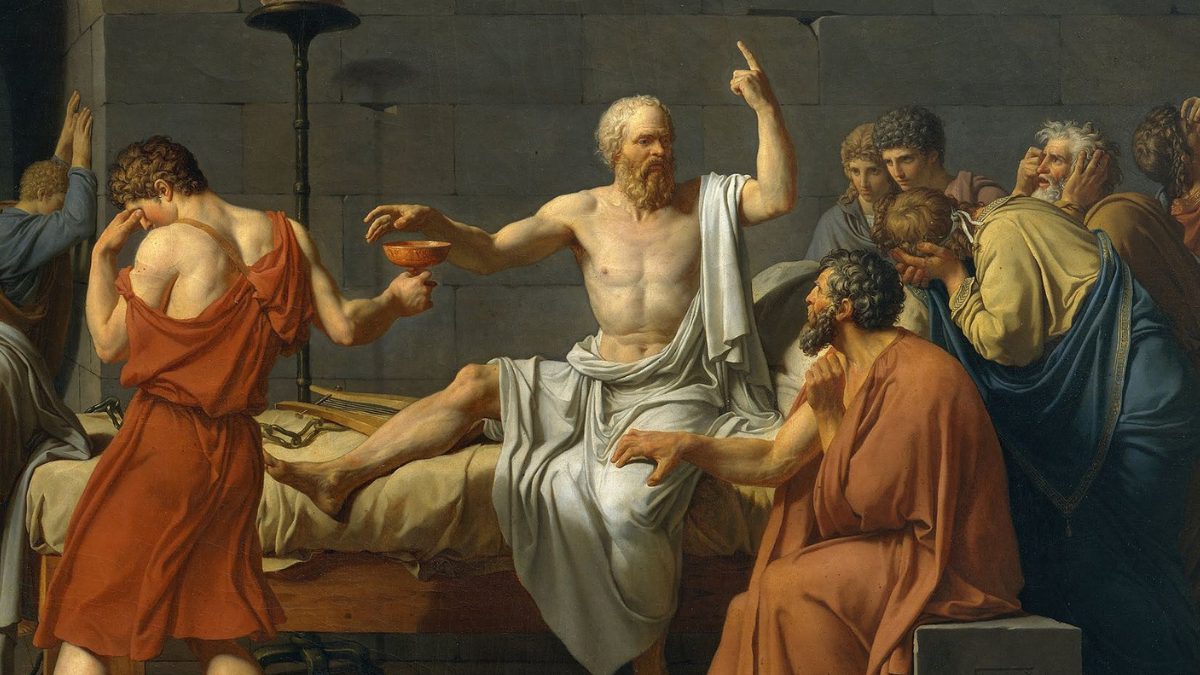

But existentialism was not just a way to dress, but more importantly a way to address a world utterly changed. Of course, the seeds of this philosophy had been planted much earlier by nineteenth-century thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche, in their unsettling explorations of the nature of existing, and novelists like Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose haunted protagonists grapple with a world shorn of certainty and divinity. No less important was the work of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, whose early twentieth-century writings, especially Time and Being, provided many of the terms and tools for French existentialists.

Primed by these works, the French existentialists burst onto the scene, stage left. The young Iris Murdoch, freshly graduated from Oxford, discovered the writings of Sartre and Camus and Beauvoir while serving with the United Nations Relief Agency in Belgium. Stunned that a public talk by Sartre attracted more people than a performance by Chico Marx, Murdoch announced she was “quite intoxicated…by the intellectual fumes.” The last time she had known such excitement, she blurted to a friend, were “the days of discovering Keats & Shelley & Coleridge when I was very young.”

How telling that Murdoch mentioned the romantics in the same breath as the existentialists. Like Shelley and Byron, Camus and Sartre proposed, in their lives and writings, a new way of being and seeing. Of course, there was the same dash of heroism, presenting the artist, alone and upright, challenging the forces of tradition and reaction, of superstition and barbarism. Yet more than a performance, their message bordered on the prophetic. In a talk he gave in New York City in 1946 and aptly titled “La crise de l’homme,” or “The Human Crisis,” Camus offered a diagnosis of this condition for those who “dwell in this still happy America and do not see this or cannot see it clearly.”

“Mistrust, resentment, greed, and the race for power are manufacturing a dark, desperate universe in which each man is condemned to live within the limit of the present. The very notion of the future fills him with anguish, for he is captive to abstract powers, starved and confused by harried living, and estranged from nature’s truth and simple happiness.”

But was existentialism truly a solution to this crisis? Not so much, according to postwar philosophers. Existentialism not only failed to offer a real solution, they held, but it even failed to pose a real question. Thus, A.J. Ayer, the apostle of logical positivism, dismissed the notion of the absurd with the wave of his thin hand, concluding that the urgent questions posed by existentialists were little more than “what modern Cambridge philosophers would call a ‘pointless lament.’” Similarly, the rationalist thinker Thomas Nagel, while agreeing that most of us, at one time or another, have been struck by the sense of absurdity, concluded that the arguments of Sartre and Camus were “patently inadequate.”

The academy’s early hostility towards existentialism was short-lived, and many departments in the United States now offer courses on the subject. What I have noticed over more than thirty years of teaching is that the number of students has grown dramatically over the past several years. Some might blame this interest on their youth, but perhaps we should blame it on the world that we, the old, have made for them. Let me suggest why this is so.

Absurdity

Let’s first turn to the absurd—a condition that even Nagel puzzled over. In an essay titled “The View from Nowhere,”—by which he means an objective view of our lives that demolishes the subjective truths we held about those same lives—Nagel concedes that, at the end of the day, “we find it difficult to take our lives seriously.” The inevitable absurdity of it all, Nigel concludes, is a “genuine problem we cannot ignore.”

Évidemment, the French existentialists did not ignore it. They held that the individual’s relation to the world—a place where we feel both at home and in exile—is one of estrangement. We are the restless composite of what Sartre described as “facticity” and “transcendence”—we are in this world, but not quite of it. It is not just, as Blaise Pascal sighed, that we are “terrified by the silence of these infinite spaces,” but that we are yet more terrified when that silence is the response for our demand for meaning.

This persistent silence bleeds into our lives, posing the question of whether it is possible, as Camus declares in The Myth of Sisyphus, “to live without appeal”—namely, without a transcendent guarantee of God or History. Such a life is very possible only if we fully shoulder the freedom we possess. In a famous public lecture in Paris in October 1945, marked by the fights and fainting in the mobbed and muggy auditorium, Sartre insisted on our absolute freedom to determine our essence. Indeed, “condemned to be free”—free, that is, to become who we are. While we have no say over our existence—we are “thrown” into the world, after all—we do have the final word over the essence. The starting point of existentialism—apologies to Descartes—is “I choose, therefore I am.”

But Sartre, despite his penchant for shocking claims about radical freedom, is lucid about its limits. We are not free, he writes in Being and Nothingness, to do anything we choose to do. “I am not free to get up or to sit down, to enter or to go out, to flee or to face danger” if what I do is “capricious, unlawful, gratuitous, or incomprehensible.” As he makes clear in various vignettes, we are always already en situation—placed in concrete and limiting situations. Hence, while my choices are finite, my freedom to orient myself toward a specific situation is still present.

Moral growth requires effort

Despite her eventual embrace of Platonism after an early infatuation with existentialism, Murdoch builds upon rather than buries this critical notion of being situated in the world. She often criticized existentialist ethics, claiming that it is based on an “empty self” making choices in superb isolation from the world and others. Yet, as the contemporary philosopher Richard Moran suggests, Murdoch’s notion of attention—that our moral growth results from the long and laborious effort to see others as they are rather than as we wish them to be—reflects the existentialist conviction that each of us “has a ‘say’ in how we orient ourselves toward the situation we confront.”

Though Moran does not cite this passage, a famous exchange between two characters in Camus’ novel The Plague illustrates his point. Raymond Rambert, a visiting journalist to Oran who finds himself trapped there when plague strikes the city, asks a doctor for a pass to leave. When the doctor, Bernard Rieux, rightly refuses the request, Rambert explodes, “But I don’t belong here!” Rieux’s perfectly existentialist reply—“From now on you do”—reminds Rambert that while he is not free to leave, he is free to choose an orientation to this situation.

Though offered a way to escape—spoiler alert—Rambert ultimately chooses to stay and join the resistance against the plague. This illustrates not just Moran’s vital point about orienting oneself in a specific situation, but also another key existentialist value: authenticity. At first, Rambert had been guilty of mauvaise foi, or bad faith—what we all do when we tell ourselves we are not free to do other than what we have always done or what we are advised to leave to others to do. This relieves us of the anxiety that comes with the realization that to live an authentic life, we recognize that we are not just free to choose, but also free to choose on behalf of humankind.

Seeking meaning

This brings us to Charles Taylor, another contemporary thinker who has engaged with existentialism. In his monumental 1989 book, Sources of the Self, the philosopher (and Templeton Prize laureate) makes the case—a brazen summary for so rich a work—for religion as the one and only true foundation for an authentic and moral life. In his subsequent (and equally monumental) 2007 book A Secular Age, Taylor expands on the earlier work and frequently mentions, with great admiration, Albert Camus. The principal text he cites is the early philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus, where the then-twenty something insists that the measure of our meaning resides in defying and not flying from our absurd condition. “For a man without blinkers, there is no finer sight than that of an understanding at grips with a reality which transcends it. The sight of human pride is unsurpassable.”

While he commends “this ideal of courage,” Taylor rightly finds it inadequate since it is not “authorized” by something outside the individual self. At the same time, however, he wrongly implies that Camus never goes beyond this “self-authorized” claim. But a glance at Camus’ own preface to the 1955 edition of the essay finds the now forty-something asserting that he has “progressed beyond several of the positions he has set down here.” In fact, by then, Camus had published his second philosophical essay, The Rebel, which though unmentioned by Taylor, does propose a stronger form of authorization—namely, the act of rebellion.

This book led not only to an explosive falling out between Camus and Sartre, but also to Camus’ essential insight into the ethical exigency of moderation. He argues that when a slave rebels against a master who denies his humanity, he repudiates his master as a master and not as a human being. By recognizing this limit, by refusing both servitude and oppression, the rebel affirms a mutual and relational authorization, one that is grounded not in the transcendent, but in the immanent. To pretend to any other kind of authorization, Camus would reply that it “impoverishes reality and relieves us of the weight of our lives.”

While we can ignore the black turtlenecks, we cannot ignore, especially now, the philosophy they represented. In 1945, the stark reality of what had just happened to the world, the staggering weight of what might still happen to the world turned young people towards existentialism. In 2025, everything and nothing has changed. My students are reading these works as if for their lives. Now as then, the claims for our freedom to act, our responsibility for those actions, and our recognition of the limits of our rebellion are absurdly urgent.