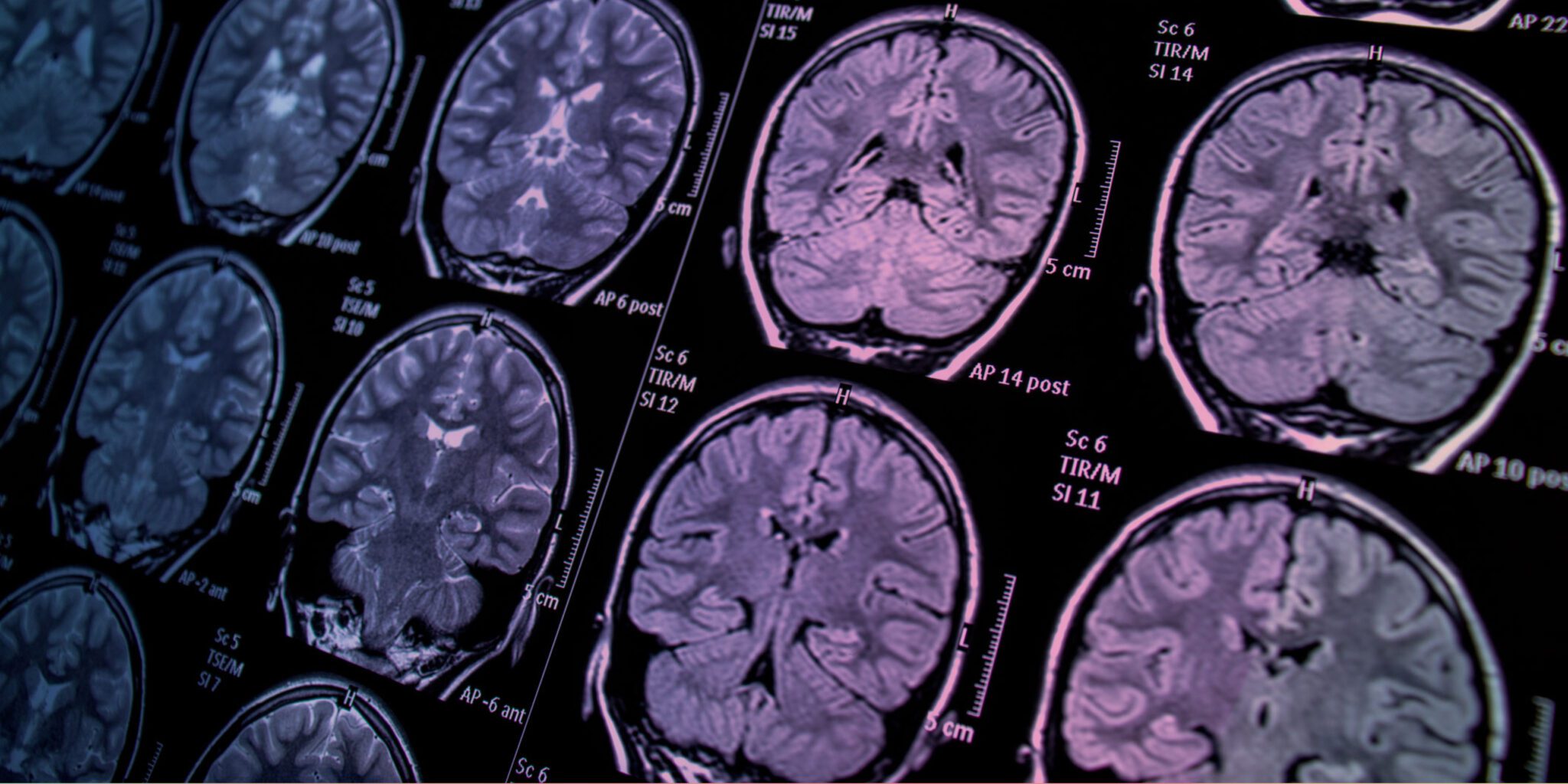

Since the infancy of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in 1990, people have been fascinated by the potential for brain scans to unlock the mysteries of the human mind, our behaviors and beliefs. Many breathtaking applications for brain scans have been devised, but hype often exceeds what empirical science can deliver. It’s time to ask: What’s the big picture of neuroscience and what are the limitations of brain scans?

The specific aims of any research endeavor depend on who you ask and what funding agency is involved, says Michael Spezio, associate professor of psychology, data science and neuroscience at Scripps College. Some people believe neuroscience has the potential to explain human cognition and behavior as a fully mechanistic process, ultimately debunking an “illusion of free will.” Not all neuroscientists agree that free will is a myth, but it’s a strong current these days. Neuroscience also has applications in finance, artificial intelligence, weapons research and national security.

For other researchers and funders, the specific aim of neuroscience involves focusing on medical imaging, genetics, the study of proteins (proteomics) and the study of neural connections (connectomics). As caring persons who are biological, neurological, physical, social and spiritual, we can use neuroscience to think carefully and understand our humanity and possible ways to escape some of the traps we’ve built for ourselves, says Spezio. Also, brain scans can enhance research into spirituality, mindfulness and theory of mind – the awareness of emotions, values, empathy, beliefs, intentions and mental states to explain or predict others’ behavior.

Averages and Neurodiversity

Predicting the behavior of one person can be problematic when looking at groups. We do brain scans across large groups of people, and we often buy into the false narrative of the average person, not acknowledging neurodiversity, says Spezio. Five thousand people can be scanned, and all those brain images are put together to get one result – an average. But the average is not an accurate representation of all the people scanned. When seeking to understand humanity in all its diversity and richness, making claims about averages can be dangerous.

Looking only at averages can turn human differences into unwarranted pathology.

In any context – work, relationships, education and elsewhere – differences are expected. For example, a child with a different kind of learning style could be pathologized, says Spezio.

Left-Brained, Right-Brained Thinkers?

Another problem involves using outdated research to create erroneous, popular theories and futuristic projections. For example, the split-brain theory was based on scientific dogma that stated the functions of the brain were separated – language was processed in the left hemisphere and emotions in the right. The ideas came from neurology prior to connectomics and have been revised. Research shows that the right and left hemispheres are deeply interconnected. The loss of interconnectivity happens when a fissure occurs, and then each hemisphere adapts and becomes more specialized. However, the incorrect and debunked split-brain theory remains popular, says Spezio.

Classes and Categories

In the past, some ideas about the brain were hyped to classify people, ranking them according to genetics, abilities and limitations – real or imagined. The result was discrimination against entire groups of people in the U.S., Germany and the Soviet Union. While that type of discrimination may sound obsolete, some researchers in current times have questioned the ability of people with autism to have theory of mind. The research was not supported by actual evidence and has created many false beliefs, says Spezio. Actually, autistic people have deep theories of mind, and most autistic people understand when they are being insulted.

Yes, We Can

In some controlled studies, brain science can tell us what a person is seeing or hearing. But the scans cannot read a person’s values or intentions beyond simple design tasks. Sometimes brain scans can predict habits. If people are shown images related to specific addictions, researchers can predict which persons are in recovery and which persons never had that addiction, says Spezio.

Further, when a person is experiencing a certain emotion or is engaged in a specific thought process, brain scans can produce images of blood flow and chemicals to localized areas of the brain. For some researchers and practitioners, understanding localization may provide perspective, increase objectivity and inspire new approaches. Specifically, educators who learn how the brain processes new information have developed new teaching methods.

No, We Can’t

Brain scans absolutely cannot tell us what a person is thinking, and the notion of mind-reading with brain scans is overstated, says Spezio. If we take brain scans into a legal context or extralegal activities to prove or disprove witness statements, then it is dangerous to believe we can see what a person is thinking. Additionally, brain scans can’t tell us what a person values.

However, we can combine brain science with formal mathematical models and theorize how the mind may work. But without mathematical models, brain scans can be misleading.

Also, brain scans alone cannot get to the heart of a person’s motivation for an action, beyond simple choices in an experiment. Yet with mathematical models, brain scans can offer insight into how many steps a person takes to understand the intentions of another person.

Psychologist and neuroscientist Russell Poldrack, Ph.D., author of The New Mind Readers: What Neuroimaging Can and Cannot Reveal about Our Thoughts, explains some of the issues related to fMRI lie detection. Experimenters work with mostly healthy young adults who are told to lie for the research. Subjects may be less motivated to mask a lie compared with a criminal defendant who may have rehearsed the lie for years. Furthermore, simple countermeasures – such as breath-holding and head movements – can skew data and make it worthless.

Potential Applications

In the future, brain scans may be used much more in health care. If a person has a sudden and inexplicable change in behavior, and if substance abuse, blood tests and potassium levels have been checked, then a brain scan could supplement other diagnostic tools.

In addition, children and three-month-old infants could be scanned – contingent upon parental permission – to identify neurological disorders so families could build supportive communities, and children could grow up understanding they began life with a different type of brain, says Spezio.

Promises and perils will continue to be part of any science. News releases are written to show the “wow!” element, but they don’t always reflect reality. What may look big and impressive may draw from only a handful of study participants. So before concluding that the latest neuroscience discoveries have settled centuries-long disputes, we must think hard about our presuppositions and our tendency to oversimplify what we struggle understand.

Rosie Clandos is a science writer and the author of Turn on Hope Street: Stories, Faith and Neuroscience.