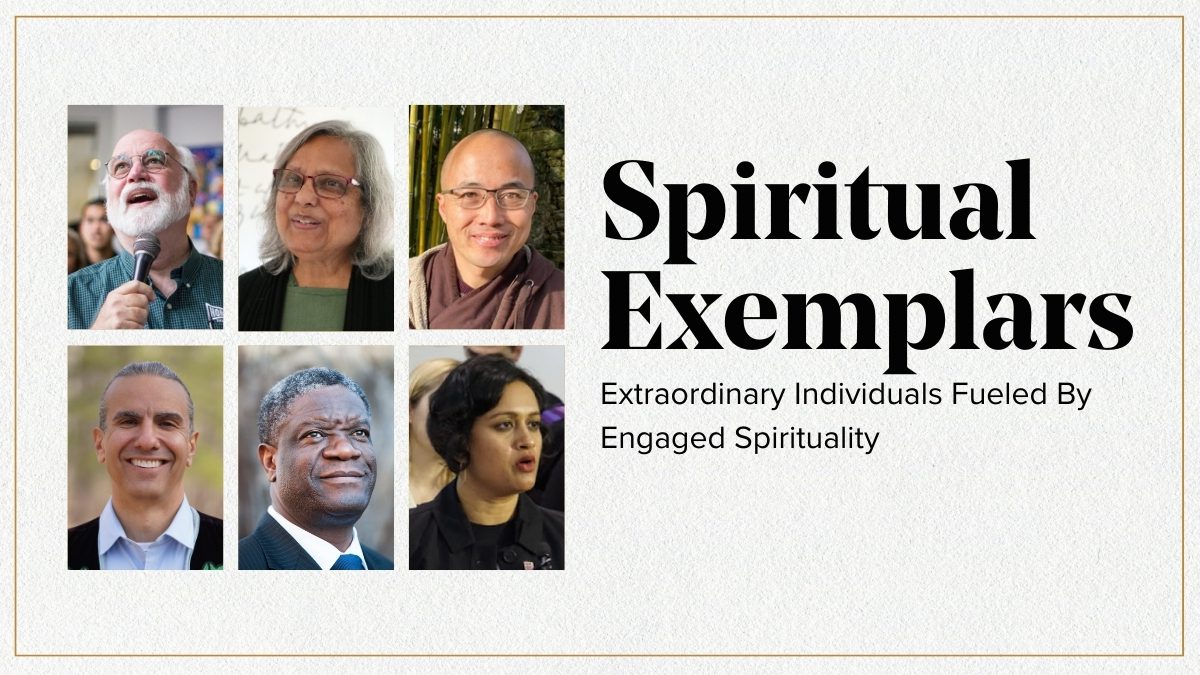

Spiritual exemplars aren’t saints, they are extraordinary individuals across the globe who are an inspiration for making the world a better place. The University of Southern California’s (USC) Center for Religion and Civic Culture (CRCC), supported by a grant from The John Templeton Foundation, has identified spiritual exemplars from around the globe, including a Nobel Prize winner, political leaders, community organizers, and others committed to the common good. These include Ela Gandhi, Father Greg Boyle, Shaily Gupta Barnes, Anton Treuer, Denis Mukwege, and Brother Phap Dung. We spoke with a few of them about overcoming anger, burnout, and systematic roadblocks to their life’s work, and discussed social justice and the spiritual practices that sustain, strengthen, and encourage them.

“Faith by itself, if it is not accompanied by action, is dead” James 2:17

No Dead Saints: Alive in Action

“During my career at USC, I’ve been fortunate to have a lot of international global projects. Traveling all over the world, I occasionally encountered a truly exceptional person who had, in many cases, started an amazing project, often focused on issues related to human rights. I made a mental note of these people,” says Spiritual Exemplars Project leader Donald Miller, Professor of Religion at the University of Southern California and co-founder of the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at USC.

“A lot of the reporting on religion is often negative. It’s about abuse, it’s about corruption, it’s about the decline of a particular institutional religion. And yet my experience was that there are these truly exceptional projects and people who, in a variety of ways, are dealing with issues of poverty, inequality, human rights, and, more broadly, the dignity of all persons, whether it be in the context of genocide or as a result of issues related to racism, or simply people, who through no fault of their own, were born into an extremely poor context,” says Miller, adding that this humanitarianism also includes healthcare, environmental justice, gender equity, peacebuilding, and more. “I thought, wouldn’t it be interesting to try to document an alternative story about religion and the role of religion.”

Inspired by this idea, a team of researchers, academics, journalists, editors, filmmakers, and others embarked on a mission to document and profile exceptional people “who were really making a difference in societies around the globe,” says Miller.

The Spiritual Exemplars project highlights 104 humanitarians from 42 countries and various faith traditions, including Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Humanism, Indigenous Religions, African Traditional Religions, Old Norse, and others. They were profiled in over 150 articles and visual stories, and highlighted in a podcast series on NPR titled The Spiritual Edge.

“There are a lot of dead saints that have been written about, but we wanted to focus on people who were alive,” says Miller. They wanted well-rounded profiles, not hagiographies. “This project is about purpose-driven human beings whose vision is enlivened through their spiritual practice.”

However, the idea of a spiritual exemplar “is highly subjective,” says Miller, adding that humanitarianism is a complex topic, especially when religion is intertwined. So, the CRCC crafted criteria for the spiritually engaged humanitarians they would be focusing on:

- A living individual anywhere in the world

- Engaged in significant humanitarian work

- Inspired and sustained by their spiritual values, beliefs, and practices

(“We left that very broad,” says Miller. There are many different traditions and various ways of accessing a spiritual connection, such as chanting, practicing yoga, meditation, prayer, being in nature, beating drums, and dancing.)

- Admired and emulated by others within and beyond their community

- Respects human rights, such as those defined by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Countercultural Changemakers

Miller says that the exemplars, in addition to being purpose-driven, tend to be compassionate, courageous, empathetic, and have an indomitable spirit – often working against severe odds. They are optimistic, persevering, and have found their identity, meaning, and purpose in serving others. “They’re also countercultural. I think that’s what makes them exceptional. I mean, they really run against the grain of ordinary human beings,” says Miller, referencing William James, who wrote The Varieties of Religious Experience over a century ago.

One of the paradoxes Miller noted about spiritual exemplars is that they exhibit qualities such as peace and joy while also feeling the despair of others so deeply.

“We didn’t call them geniuses, and we also didn’t label them as saints, but exceptional people who went against the grain of a lot of societal norms in the sense that they had a vision for social change at a lot of sacrifice to themselves…They pursued that vision, which is where the grit and perseverance play out,” explains Miller.

Diverse Pathways

“I interviewed Father Greg Boyle of Homeboy Industries. He’s a Jesuit. And early on in his life, he chose to pursue that as a religious calling. Then, he ended up founding Homeboy Industries, this incredible project. But other individuals found their path almost accidentally,” says Miller, sharing about Julie Coyne, who went to Guatemala to study Spanish and went on to form a preschool for extremely poor indigenous children.

“I interviewed Father Greg Boyle of Homeboy Industries. He’s a Jesuit. And early on in his life, he chose to pursue that as a religious calling. Then, he ended up founding Homeboy Industries, this incredible project. But other individuals found their path almost accidentally,” says Miller, sharing about Julie Coyne, who went to Guatemala to study Spanish and went on to form a preschool for extremely poor indigenous children.

There is Jean Gakwandi in Rwanda, a survivor of the 1994 genocide who lost most of his family, “but his way of dealing with the trauma of the genocide was to create Solace Ministries,” says Miller.

Many exemplars believe they’re the medium by which God’s work is done. “Sister Rosemary [Nyirumbe] in Uganda told me, ‘I’ve never started a project because I had the money or the resources. I believe in a provident God.’” Miller added, “She’s very observant in her prayer life. A kind of renewal happens daily in terms of confronting the issues she is working with. Engaged spirituality is to engage in your everyday life…projects and programs grow as one responds to the situation’s needs and is inspired by the vision.”

Many exemplars believe they’re the medium by which God’s work is done. “Sister Rosemary [Nyirumbe] in Uganda told me, ‘I’ve never started a project because I had the money or the resources. I believe in a provident God.’” Miller added, “She’s very observant in her prayer life. A kind of renewal happens daily in terms of confronting the issues she is working with. Engaged spirituality is to engage in your everyday life…projects and programs grow as one responds to the situation’s needs and is inspired by the vision.”

“It’s not just highfalutin spiritualism,” says Miller, calling out those who focus solely on abstract religious and moral principles such as gratitude or love. “This is physical work.”

Stories have a huge potential power to enliven our imagination about what is possible, perhaps incrementally at first, with the possibility that the service will blossom. Miller’s hope is that the exemplars’ stories will inspire others.

“This work also transforms the exemplars themselves. They are renewed often in the work,” says Miller. “There’s a reciprocal effect.”

With Every Exemplar, a Community

Exemplar Anton Treuer, Professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University in Minnesota, is known for his local and global work on equity, education, and culture.

Exemplar Anton Treuer, Professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University in Minnesota, is known for his local and global work on equity, education, and culture.

“I think there has been, throughout the Western world, a heavy and increasing emphasis on individualism, up-by-your-own-bootstraps, entrepreneurial spirit, drive, and ambition. Those things can serve very positive purposes. But they’re also completely at odds with how human beings have made things work for millennia,” says Treuer. “If you go back even just a few thousand years ago, all of us are tribal humans. We’re all living in villages. We didn’t survive because we outcompeted the person in the next cave or accumulated more resources than them. We survived because the people in the next cave loved us and would intervene if we were in trouble. So, we are hardwired to need and crave connection, community, belonging, love.”

He shares that those who are very successful by Western standards “have every advantage and privilege, yet have become disconnected from one another and even themselves. This existential angst drives a lot of struggles with spiritual and mental health and well-being,” says Treuer. “My spiritual practice helps me to reconnect.”

“It is not enough to just navigate systems but to work to change those systems to render them more equitable. The more we act in alignment with our spiritual values and principles, and the more that we act not just with performative humility and performative niceness, but with genuine kindness and a genuine desire to serve others, the greater the good we will be able to accomplish.”

The Exemplar in You

Shaily Gupta Barnes is the Policy Director at the Kairos Center for Rights, Religions and Social Justice and the Poor People’s Campaign. She has a law, economics, and international development background, working for marginalized communities to remedy poverty, racism, ecological devastation, and militarism. She’s addressed the water crisis not just in Flint, Michigan, but the water affordability crisis across the United States.

Shaily Gupta Barnes is the Policy Director at the Kairos Center for Rights, Religions and Social Justice and the Poor People’s Campaign. She has a law, economics, and international development background, working for marginalized communities to remedy poverty, racism, ecological devastation, and militarism. She’s addressed the water crisis not just in Flint, Michigan, but the water affordability crisis across the United States.

“I believe that anyone and everyone has the ability to make the kind of commitments that I and others [on the Spiritual Exemplars list] have made,” says Barnes. “I have to hang my hat on that hope because I’m trying to build a huge social movement that will require many, many leaders.”

“You need a community of people that you’re building this with. It’s the people I talk to every day, the people I’m in touch with and whose work is making a difference on the ground, those are the people that keep me going,” says Barnes. “We’re committed to a vision of a world that is better, and that is possible, and we’re also deeply committed to each other. We can’t afford failures and losses, so we fight for each other.”

Social justice work is often tedious—back-and-forth scheduling, administrative tasks, etc. “It’s not just in the streets with all the intense emotions…A lot of it is just this daily relational building, and that takes time,” says Barnes. “Ella Baker famously said the ‘spadework’ of a real movement is cultivating the kind of leadership and the community around that leadership that can sustain, develop, and replicate itself…leaders aren’t just kind of born; they’re forged out of struggle, community, and commitment.”

Barnes speaks about dharma, the Hindu concept of duty, and identifying the kind of commitment you need to make for your life. Adding that this takes real honesty with yourself about your strengths and weaknesses.

“What can I do in this moment? Not the moments that are behind me or in front of me. What are we building right now? It may be a little scary to take the risk and step outside of and challenge what you think you know,” says Barnes. “And I think there’s something very intuitive about the process of discernment. Listening with your gut, heart, or something that’s pulling you in a certain way.”

She suggests starting where you are – with the people around you. Ask questions like, what is happening in my community? In my city? In my county?

“Identify and get involved in different programs at a grassroots level. Just take a step out into this world and see where that takes you,” says Barnes, adding that these programs are often at public spaces such as libraries, schools, churches, and other religious houses of worship. “Put yourself in the position of being next to those who are confronting injustice and being with them in those fights, listening, learning, and then identifying what your role is from there.”

“I believe in the God or goddesses of justice…what they want most is for justice to reign… There’s this fierce battle for saying that I matter, my community matters. I, too, reflect the divine, and I am deserving, and we are deserving of having a life that is worthy of what God intends for this world,” says Shaily.

She often thinks about a prayer adapted from other prayers to Lakshmi, who is often worshiped in the Hindu tradition as the goddess of wealth but also represents well-being, freedom, love, and duty. Barnes incorporates community well-being and the ability to be free of injustice.

“Lakshmi, born out of struggle, calls us to be guided to a world of plenty where there is no hunger, there is no thirst, there is no homelessness. Where we have refuge from poverty, war, fear, and violence, where all needs are met, and maybe most importantly, where peace and love are abundant… that’s where we’ll find freedom. That’s where we’re going to find liberation,” says Barnes. “I have three children, and I think about the world they’re growing into. I want them to have childhoods. I want them to have clean air and good food and not have to worry whether their job will pay them enough to have a nice home. And then for them to want to have children in the future and not be so scared that this world is not a place where another generation can survive. That’s the kind of world I want, not just for my children, but for all children, that we should have that kind of peace and love.”

Alene Dawson is a Southern California-based writer known for her intelligent and popular features, cover stories, interviews, and award-winning publications. She’s a regular contributor to the LA Times.