This story is Part I of a three-part series drawing on research related to The Science of Immortality. Stay tuned for the release of Part II in May 2022.

Around 100,000 years ago, humans living in the region that would come to be called “Israel” did something remarkable. When members of the community died, those left behind buried the dead in a cave, placing some of the bodies with great care and arranging them near colorful pigments and shells. Although burial is so common today as to be almost unremarkable, for ancient humans to exhibit such behavior suggested a major development in cultural practices. The Qafzeh Cave is one of the oldest examples that humans understand death differently than many other creatures. We seem to have an innate desire to mark it with ritual.

It is an unavoidable fact of biology that all organisms die, whether by disease, disaster, or simply old age. Yet our species, Homo sapiens, seems to be the only creature blessed—or cursed—with the cognitive ability to understand our mortality. And thanks to our powerful intelligence, we’re also the only beings to imagine and seek out death’s opposite: immortality.

In religious traditions, spiritual afterlives and reincarnation offer continuation of the self beyond death. In myth and legend, sources of everlasting life abound, from the Fountain of Youth to elixirs of life. Some people seek symbolic immortality through procreation. Others aim for contributions to society, whether artistic, academic or scientific. And still others have pushed the bounds of technology in search of dramatic life extension or a digital self.

Where does this impulse come from? Do we seek afterlife paradises simply to soften the unfathomability of death? For some social psychologists, the answer is ‘yes.’ Terror management theory, developed in the 1970s and ‘80s, suggests that our knowledge of death directly influences our behavior. We plan for the future in such ways that aim to increase our longevity, such as wearing sunscreen to avoid skin cancer, or seatbelts to prevent death in car crashes. We’ve also created cultural practices that allow us to feel a sense of self-worth and control over what might otherwise be a world of chaotic randomness.

But for Deborah Kelemen, professor of psychological and brain sciences at Boston University, terror management only goes so far in explaining this aspect of human behavior. To understand if our immortality impulse is based entirely on cultural beliefs around fear of death, or if comes from a more innate part of our neurology, Kelemen looks at children instead of adults. The challenge is separating what kids imbibe from the world around them versus what happens as a natural result of brain development.

“There is so much secular as well as religious testimony about what it is to be a ghost,” Kelemen said. “You see it in Harry Potter films, in Disney films. Even if children aren’t being raised in religious homes, they’re surrounded by cultural ideas that would tell them what to believe, and that’s true from very early on.”

-

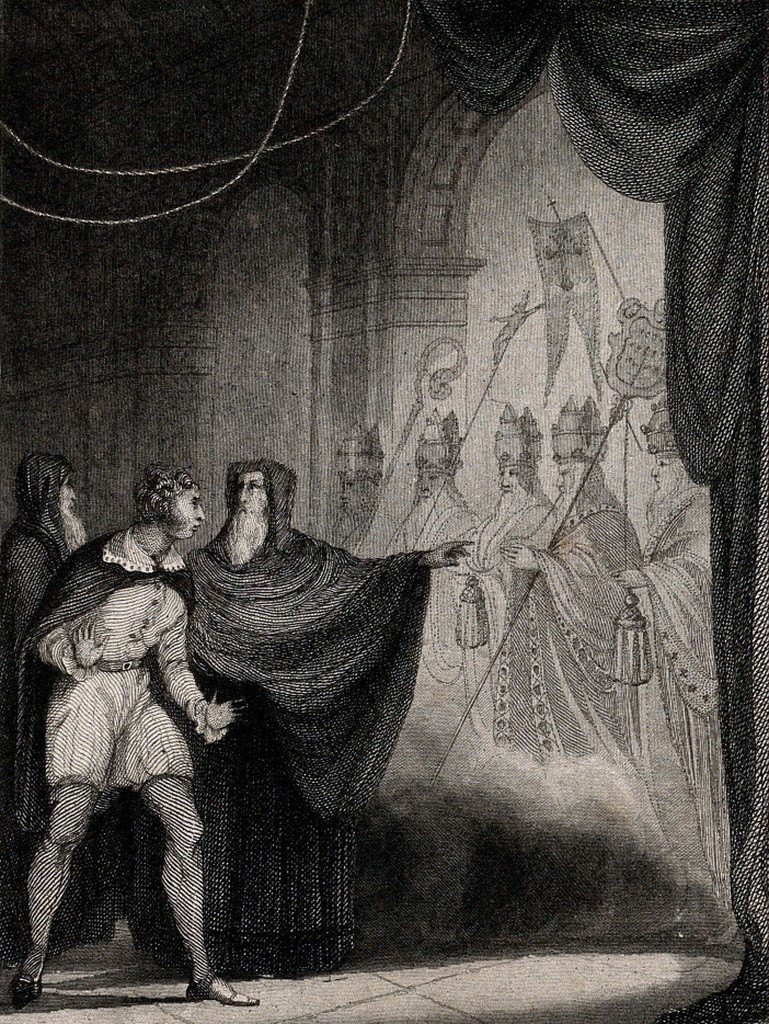

Ghosts appearing to a young man. Engraving by B. Winkles after J. Salmon (approx. 1875)

Kelemen theorized that terror management explained some aspects of adult behavior, but wanted to know whether children adopted a fear of death and a longing for immortality through social means, or if it happened more intuitively.

To investigate these ideas, Kelemen assisted post-doc researcher Natalie Emmons in a study on pre-life beliefs. Instead of asking children about the concept of immortality as an event that only occurs after death, Emmons created a questionnaire about whether the children existed in any form before they were born. She then interviewed more than 200 urban children in Ecuador (who were largely raised in a Catholic context) and around 80 children in a Shuar village of indigenous people.

Emmons found that, despite differences in cultures, the children consistently stated their belief in an emotional existence before they were born. They stated that before their birth, they felt sad to not be with their families yet, but happy that they soon would be. For Kelemen, this is evidence that our brains seem to be cognitively wired to intuit the concept of immortality.

“It’s hard to imagine a point in time when you had no social connection, and it’s hard for us to imagine not feeling,” Kelemen said. “The notion of ‘I think, therefore I am,’—it’s more like ‘I feel, therefore I am.’” And these intuitive feelings that are present in children from a very young age, which might provide fertile ground for the development of religious beliefs.

And these religious beliefs have been an enduring element of human civilization for thousands of years. In the Abrahamic traditions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), concepts of Heaven offer rewards to faithful, dutiful believers. Though the precise details of the afterlives vary from one tradition to another, they’re united by the concept that death is a temporary disruption rather than a termination of the self. The body may no longer be physiologically functional, but some inner essence—a soul or spirit—has enough shared characteristics with the person in life as to still be considered the same being after crossing death’s threshold.

But in Buddhist philosophy, the exact opposite is a central tenet. Instead of striving for individual immortality, Buddhists seek to accept the principles of “no self” and universal impermanence. Yet the ability to truly internalize these ideas seems to be particularly challenging.

In a study on religion and ethics, Jay Garfield and a team of researchers found that even practicing Tibetan monks were more fearful of self-annihilation than Hindus or those following an Abrahamic religion.

“We were surprised by that result,” Garfield said. The researchers theorized that engaging in regular contemplation of one’s mortality, as is the case for Tibetan Buddhists, may initially increase fear of death, especially because that death is final, according to their religious and philosophical beliefs.

On the other hand, Garfield theorizes that Buddhists who continue deepening their meditation practice may come to a real acceptance of mortality. For practitioners who have meditated more than 10,000 hours, there might be a deeply internalized sense of selflessness that ultimately provides greater wellbeing. But he hasn’t yet been able to gather sufficient empirical evidence for his hypothesis, leaving it an open question.

“Does the recognition of selflessness assist in dealing with fear of death? Does it do things like increase generosity? We just don’t know,” Garfield said.

For those who eschew Abrahamic beliefs and don’t want to rack up 10,000 hours of meditation, another approach to death might be found in science, technology, and medicine. But even given their impressive track record of creating things once thought impossible, our desire for more time on Earth faces major obstacles.

Stay tuned for the release of Part II of the Immortality Series in May 2022.

Lorraine Boissoneault is a Chicago-based writer covering science and history. She is the author of the narrative nonfiction book “The Last Voyageurs.”