This story is the first in our series about what extremely ancient human societies can teach us about what it means to be human. Too often, we regard “Stone Age” peoples as primitive, not just technologically, but psychologically, even though they are biologically identical to modern humans. Perhaps, by stripping away the technologies that have accrued over the subsequent millennia, we can see ourselves more clearly.

For nearly three decades, excavations at Göbekli Tepe have hypnotized the public, thrilled tourists, and stymied archaeologists

In German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt’s preliminary report on excavations at Göbekli Tepe, one gets the impression that the eminent scholar is grappling with a site too enigmatic to comprehend. The astounding collection of monoliths predates the Pyramids of Giza by almost 8,000 years; they’re utterly unlike anything archaeologists had ever seen before.

“Since Göbekli Tepe is a place that is not comparable with the very large range of known Neolithic sites in the Near East, this report will be a little speculative in some aspects,” Schmidt wrote in 2000. “It is not possible to lay down exactly essential data as is usual in scientific reports. It is not due to insufficient work, but to the specific situation at Göbekli Tepe.”

This corner of southeast Turkey is part of a swathe of territory associated with some of humankind’s most momentous societal shifts. Though the landscape around Göbekli Tepe is a dry plateau today, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that formed the Fertile Crescent of Mesopotamia are only a few hundred miles away. In this landscape, the Sumerians first developed writing 5,000 years ago; some of the earliest evidence of domesticated grain comes from Nevali Çori, a 10,000-year-old settlement in Turkey.

Aerial view of the Main Excavation Area (Southeast-Hollow) Courtesy of Göbekli Tepe Project

But at Göbekli Tepe, Schmidt uncovered something almost incomprehensible. Buried in mounds of animal bone and rock were more than 20 circular stone enclosures. The largest measured 65 feet in diameter, with two 18-foot-tall limestone pillars dominating the center of the enclosure. At nearly the height of a two-story house, the massive T-shaped pillars are decorated with carved arms, hands and fingers, plus ornate fox skin belts around their waists—but no clear facial features.

All around the site are sculptures and carvings of fearsome creatures: spiders, scorpions, vultures, wild boars, and a kneeling figure carrying a human head in its hands. The largest monoliths are thought to weigh more than 16,000 pounds and have been dated to 12,000 years ago—the final days of the Ice Age, when glaciers were beginning to retreat from Europe. The site is so old, humans hadn’t yet developed pottery or domesticated any plants or animals for food. For the artists working at Göbekli Tepe, the only tools available for carving the massive limestone monoliths were other stones. To complete such monumental works of architecture required an almost unfathomable amount of work, the prehistoric equivalent of digging a tunnel with spoons. But the work wasn’t just time-consuming; it was also an awesome display of artistry and skill.

The question becomes: why did a group of hunter-gatherers spend so much time, energy, and resources on enclosures that don’t seem to have been for any practical purpose? What was the point of this massive architectural and artistic undertaking? For Schmidt, one vague answer suggested itself.

“Beyond ‘ritual’ we don’t know the exact function of the site,” he wrote. “We don’t know what ideas were intended to be expressed by the T-shaped pillars, which clearly seem to have an anthropomorphic design… We don’t know if Göbekli Tepe really is a unique site, or if similar unexplored sites exist in other regions, or how far apart such places would be.”

Even with his uncertainty, in 2008 Schmidt published a book called They Built the First Temples. This, according to archaeologist Trevor Watkins, was the title that launched a thousand hyperbolic headlines. A specialist in Neolithic archaeology affiliated with the University of Edinburgh, Watkins had a close working relationship with Schmidt. But Watkins was appalled when the German press named Göbekli Tepe “the Garden of Eden.” Publications ranging from Smithsonian Magazine to National Geographic designated the structures as the world’s “first temples”—despite there being no way to prove these enclosures were related to religious beliefs.

“The idea of ‘gods and temples’ goes from journalist to journalist,” Watkins says. Those stories perpetuated an understanding of Göbekli Tepe that isn’t quite correct. Only about 10 percent of the site has been excavated, and it’s too early to draw such sweeping conclusions. The appearance of anthropomorphic gods, religious practices, and shared iconography are notoriously challenging to evaluate scientifically.

Watkins uses the example of a Byzantine church filled with mosaics and murals. To someone acquainted with Christianity, the cross, the depiction of Christ and his disciples, and the symbolism associated with Heaven and Earth will be recognizable. But drop someone with no knowledge of Christianity into that same church (a difficult proposition in the 21st century), and she’ll have no way of deciphering the meaning behind the art.

For modern archaeologists to make sense of the Neolithic carvings at Göbekli Tepe is equally inconceivable. We simply don’t have the cultural context to say “this

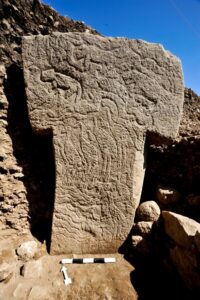

Pillar 56 in Building H is adorned with low reliefs of wild animals, reptiles and birds covering its entire south-facing broad side Courtesy of Göbekli Tepe Project

scorpion is a symbol of craftiness” or “the presence of vultures means they worshipped bird gods.” In fact, Göbekli Tepe completely predates religion as we know it. Researchers have proposed that the existence of moralizing gods, like the ones we’re familiar with, didn’t appear until 3000 B.C. Though 5000 years in the past sounds like ancient history, it’s a period closer to our own time than it would’ve been to the hunter-gatherers of Göbekli Tepe. Those monument builders lived 7000 years before any moralizing gods appeared—and yet, they seemed to have a clear sense of the inexplicable, the supernatural, the otherworldliness of the world around them.

To get a better idea of how our ancestors may have understood the supernatural, a group of researchers looked at 33 modern-day hunter-gatherers and their ritual practices. Although it might be impossible to extract backward from current practices, the researchers did find aspects of religion permeating the daily lives of these people—though not the kind of organized religion we see in Abrahamic traditions. The unifying factor for all the groups was animism, an “innate cognitive trait [that] allows us to attribute a vital force to animate and inanimate elements in the environment. Once that vital force is assumed, attribution of other human characteristics will follow.”

Given that humans occupied Göbekli Tepe so long ago, it’s hard to fathom the precise purpose of the site. Carving and erecting the monoliths would’ve taken an enormous amount of work and a significant number of laborers; they were clearly motivated by some important purpose. And the enclosures certainly would’ve created an intense emotional response, Watkins says. He and others have hypothesized that the circular structures were fully enclosed, with entrance holes on top.

“The only light is through a trap door in the roof,” Watkins says. “A lot of that iconography is not intended to make you feel comfortable.”

No human today can understand the exact references being made in the Göbekli Tepe sculptures. But it’s not hard to imagine the way one might feel being dropped into a dark, circular enclosure, surrounded by the faceless monoliths and the leering images of scorpions and spiders and boars. It would create a sensation of being entombed with monsters, perhaps spurring terror, but also a surge of bravery. Would there have been chanting, or drumming, or alcohol-induced intoxication? We may never know, but it’s not hard to imagine.

As for their lives outside this ritual space, there are some things we can discern based on the archaeological record. These weren’t grunting cave-dwellers like those that sometimes appear in the popular imagination. Hunter-gatherers of the period had close social ties with people around the region and were exchanging goods like obsidian and seashells from far-off distances. The design of three circular structures at the site creates a nearly perfect equilateral triangle, which suggests they created a scaled floor plan before construction. Traces of wild grains found on more than 7,000 grinding tools from the site suggests the builders were making beer or bread, and possibly cultivating wild crops in the area. And the presence of human skulls with traces of carving and the application of red ochre on them suggests there was some preoccupation with death, potentially as an aspect of ritual practices or beliefs.

Building D Courtesy of Göbekli Tepe Project

To learn more, the site will need to be more fully excavated. Due to the untimely death of Schmidt in 2014, leadership of the project passed to Lee Clare and has continued with oversight from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. In 2018, Göbekli Tepe was added to the Unesco World Heritage register. In 2019, the Turkish tourism office declared it the “Year of Göbekli Tepe,” and Culture and Tourism Minister Mehmet Nuri Ersoy referred to the region as “the pyramids of south-east Turkey.” The future of Göbekli Tepe—and the insight it may still offer about ritual practices among Neolithic hunter-gatherers—may well be balanced with its role as a source of tourist revenue for the region.

Whatever discoveries may still lie beneath the ground, Watkins can testify to its magnetic quality. More than ten years ago, he was leading archaeological tours of the region, and remembers visiting Göbekli Tepe before it had been renovated to make it a more accessible tourist site. During a quiet moment, Watkins ran into several people who weren’t part of his group: a motorcyclist from Spain, and a mother and daughter from Vancouver, Canada. All three had made the journey to Turkey to see Göbekli Tepe based solely on magazine articles they’d read about the place.

Watkins felt stunned that they’d traveled so far to see something that archaeologists still didn’t understand. The immensity and the mystery of the site seems to exert a palpable force over people. As for the original purpose of Göbekli Tepe, as conceived by its creators, Watkins can’t say for certain.

What seems clear is that these people were as human as we now are. Faced with our modern world, they might be shocked by cars or planes or even the grocery store. But they did share a sense of the sublime, the fantastic, the transcendent. With their limited tool technology, they dedicated themselves to immense works of art. Their lives weren’t limited to hardscrabble survival; they, too, explored what it means to be subject to forces beyond our control.

Read Part II and Part III of the series, which focus on Çatalhöyük.

Still Curious?

Learn more about research we’ve funded on Cultural Evolution, one of our twelve strategic priorities.