This story about Çatalhöyük is the second installment in our series about what extremely ancient human societies can teach us about what it means to be human. Too often, we regard “Stone Age” peoples as primitive, not just technologically, but psychologically, even though they are biologically identical to modern humans. Perhaps, by stripping away the technologies that have accrued over the subsequent millennia, we can see ourselves more clearly. Click here to read the first story in the series, which explores the world of Göbekli Tepe.

A historian once told me, “You can tell what a society values by looking at its biggest buildings.” In medieval Europe, cathedrals towered over nascent cities. In our age, corporate headquarters and entertainment venues dominate our city centers. Without knowing a word of the local language, a keen observer can start to piece together what animates and inspires the inhabitants of a community.

We are in this position when we consider the countless number of prehistoric societies who had no written language and no surviving descendants to tell their stories. Human history, as we know it, is largely an account of those who were powerful enough to build empires and leave indelible marks on the surface of our planet. Societies without written records or substantial physical infrastructure melt into the past, leaving only fragments for future generations to reconstruct their lives.

While the power to build, conquer, and rule holds a certain fascination, it is different from enabling people to live well. In an age of political and environmental crises, many wonder if there are alternative ways of living that can lead to social harmony and individual flourishing. What other paths have humans taken during the long history of our species? What can we learn from our forgotten ancestors that could be valuable to us today?

Rather than think of humans purely as producers and consumers — defining groups as hunter-gatherers or agriculturalists — we’d like to understand what made prehistoric societies distinctive. What did they desire and strive towards? What did they find beautiful? What gave their lives meaning and purpose? If we regard prehistoric humans as real people, we might uncover that their lives had a richness and multi-dimensionality that rivals our own.

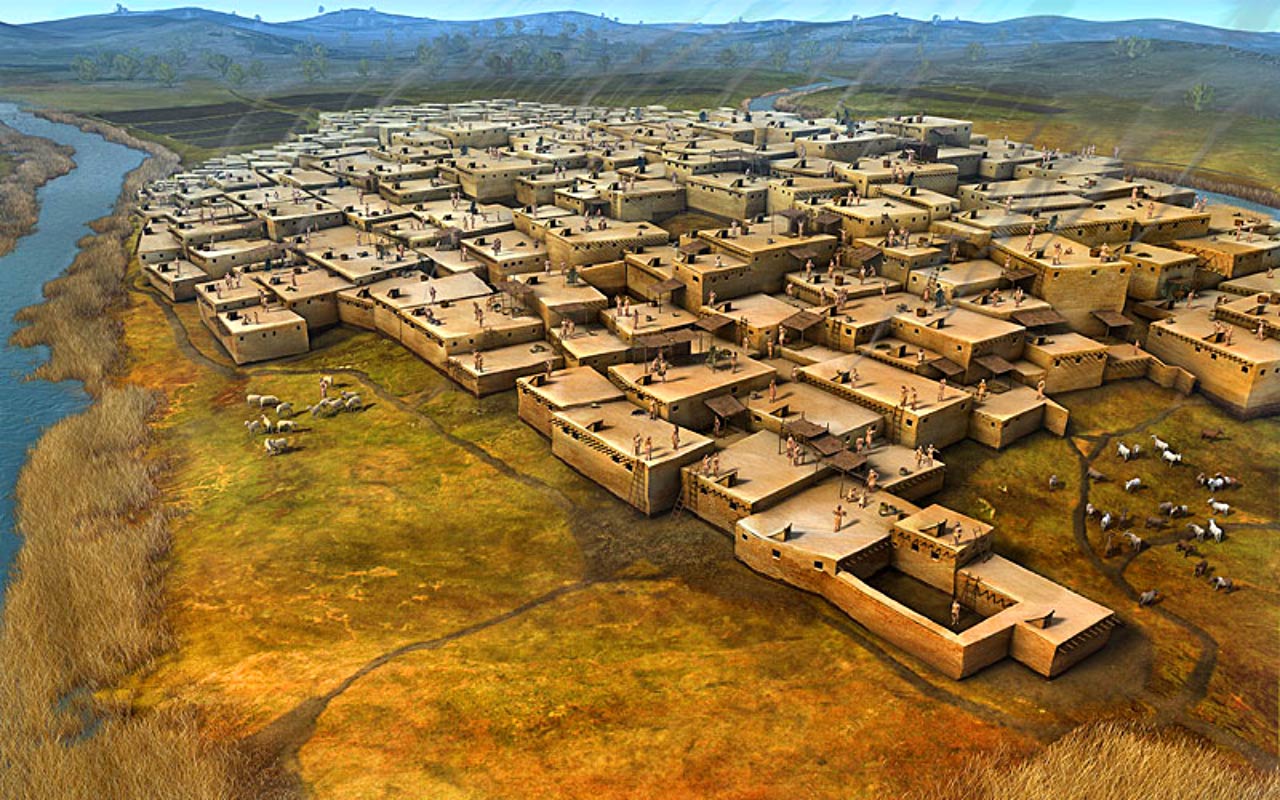

Çatalhöyük: A city with no rulers, no police, no courts

What’s special about Çatalhöyük? It was a city that existed 5000 years before the Egyptian pyramids were constructed. It endured in a single

The Excavation of Çatalhöyük

place for 1500 years. It persisted in the face of disruptive technological innovations such as the advent of the copper age. After the city was abandoned, it lay undisturbed for nearly 8000 years, leading to a nearly unprecedented preservation of the details of individual households. Each home had extensive art and adornments — bull horns, leopard sculptures, plastered skulls — and the community had a fascinating way of relating to death.

Scientists have focused on Çatalhöyük for its rich, strange detail of a vanished way of being human—one that could point to alternative futures. The John Templeton Foundation was an early supporter of this work over two decades, motivated by a desire to understand the deepest roots of humanity’s quest for meaning, to mine insights on how cultures evolve, develop, and thrive.

Çatalhöyük, in modern day Turkey, was first excavated in the early 1960’s, then again, starting in the 1990’s by an international team led by archaeologist Ian Hodder. Hodder and his colleagues have conducted over 25 years of continuous research of the site, leading to a prodigious amount of data that they continue to process. The variety of artifacts is staggering, and the interpretation of their significance has evolved as scientific techniques and theories have matured.

Hodder’s group found that in this town of several thousand people who occupied the area continuously for over a thousand years, there were no public plazas, temples, or other administrative buildings. There is no evidence of any centralized institutions to “govern” thousands of people.

Emeritus professor Trevor Watkins, after four decades of studying Near Eastern prehistoric societies, including a related site called Göbekli Tepe, continues to be astounded, “How did a population of several thousand people live like this for over a millennium? They were not subservient to a ruler, there were no police, no courts. This was not a band of hunter-gathers. It was small-scale, independent society that managed completely on their own.”

Source: Courtesy of Elelicht, distributed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Hodder’s team found that all of the structures they excavated at Çatalhöyük had evidence of residential activity inside of them. Some of the homes — which Hodder has named “history houses” — were more elaborately decorated than others. They were occupied the longest amount of time, had the most decorations, and contained the most burials. But even these households did not exhibit greater control over production and storage of food or other essential resources—they were not richer or more powerful in a material sense.

While Çatalhöyük was egalitarian in this respect, differentiation among the members of the community could be expressed socially and reputationally. Archaeologist and emeritus professor Brian Hayden points out that trade in prestige items like obsidian and seashells could have been used to grow social status and manipulate others. We must be careful not to romanticize Çatalhöyük as being completely free of power inbalances, he warns.

Hodder himself has noted, “These history houses aggrandize over time. Then tended to become more elaborate over two-to-three-hundred-year period. Then they suddenly stop. There’s evidence that some of them were even burned. Then the cycle started up in another location again.”

Humans being what they are, a certain percentage of people, both prehistoric and modern, has a strong self-aggrandizing tendency. This is a corrosive force that threatens equality and stability within a community.

What’s remarkable about Çatalhöyük is not that they were able to eliminate this all-too-human trait, but that they were able to keep it in check through their social structures, norms, and rituals. They achieved a dynamic balance between the egalitarian and aggrandizing tendencies for well over a millennium.

Read Part III of the series about Çatalhöyük.

Still Curious?

Learn more about research we’ve funded on Cultural Evolution, one of our twelve strategic priorities.