This story about Çatalhöyük is the third installment in our series about what extremely ancient human societies can teach us about what it means to be human. Too often, we regard “Stone Age” peoples as primitive, not just technologically, but psychologically, even though they are biologically identical to modern humans. Perhaps, by stripping away the technologies that have accrued over the subsequent millennia, we can see ourselves more clearly. Click here to read Part One of the Çatalhöyük stories.

As different as the ancient, egalitarian city of Çatalhöyük was from ours, it is relatable in other respects. Archaeologist Trevor Watkins from the University of Edinburgh has observed, “Their house and home life is very familiar. They lived in rectangular, mud brick structures with plaster walls. They made their houses into homes by adorning them with decorations, making changes whenever it suited them. There’s not a huge leap from that to the home remodeling television shows that are so popular today.”

Stanford University professor Ian Hodder, who has spent over two decades excavating and studying Çatalhöyük, is also convinced of the importance of domestic life there. But we should be careful not to assume that their social organization was just like ours. Evidence retrieved from burial remains indicate that people who lived together were not always closely related: “They lived together like families, but not biological families. They remind me more of 1960s communes. The houses were more permeable that we previously thought — their members could move in and out.”

So, what did several thousand people living together in Çatalhöyük do each day? Since the Neolithic has often been portrayed as the period of agricultural revolution, it’s easy for us to imagine these residents behind heavy plows, hauling huge loads of grain to feed swelling populations.

But actual human history is not a sharp dichotomy between hunter gatherers and intensive agriculturalists — this society did not exactly match either category. Trevor Watkins describes more precisely, “Çatalhöyük did not employ draft animals. They had no carts or wagons. Cultivation and transport were done by hand. It’s better to think of this lifestyle as garden agriculture.” In addition to the direct cultivation of food, they kept livestock, gathered wild plants, and hunted animals, enabling a highly diverse diet.

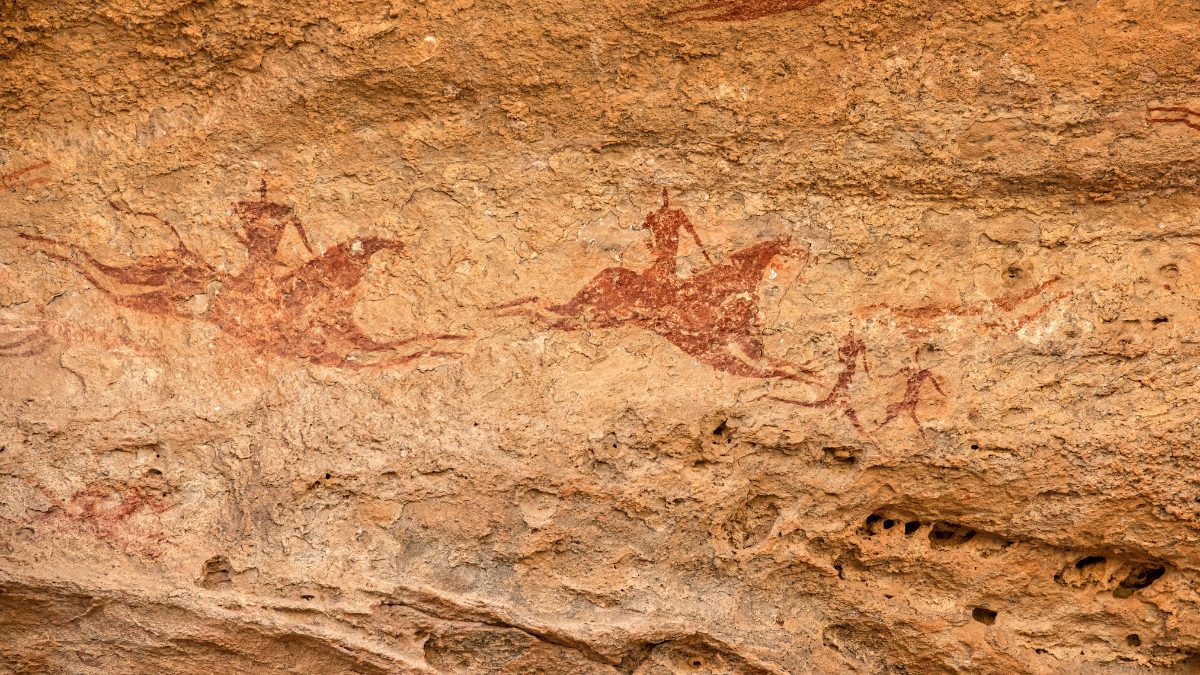

Source: Courtesy of Elelicht, distributed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Inside their individual homes, residents cooked, slept, and socialized. Artwork was prominent — wild bull horns protruded from the walls, plaster surfaces were painted with depictions of wild animals, and sculpted figurines rested on hearths.

Ever since British archaeologist James Mellart first excavated Çatalhöyük sixty years ago, scholars have speculated whether the artwork represented supernatural beings. Jacques Cauvin, author of the influential work The Birth of the Gods and the Origins of Agriculture argued that the corpulent female figurines represented a goddess, and the wild bull a god. Given the preponderance of the bull motif in subsequent societies in the Near East, it is certainly an interpretation worth taking seriously.

However, in the decades following Cauvin’s thesis, scholarly views have shifted. Trevor Watkins, who translated Cauvin’s book into English, thinks differently now: “Çatalhöyük existed in a period of pre-religion. Reading gods into their society is anachronistic. We can be more confident that these people knew stories that explained the world they inhabited.”

Having a narrative account of how the world came to be and how we fit into it seems to be an essential part of being human. Though the details have changed over time, this need for understanding still captivates us today, whether it is articulated in religious or scientific terms.

Though it is notoriously difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain the precise worldview of a prehistoric people who left no written accounts, the archaeological

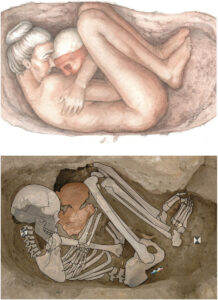

Image credit: Çatalhöyük Research Project

record still provides us with certain clues. For Hodder, examing the evolution of the city’s culture, he observed: “There’s a historical trajectory in Çatalhöyük from wild bulls to well-fed women. Their sacred symbols shift away from hunting prowess toward revered mothers who bear many children.” We might infer from this evidence that the residents’ conception of prosperity and the good life shifted along similar lines.

Whether the members of Çatalhöyük actually worshipped a god or gods is a matter of speculation, but their awareness of some sort of spiritual power is evident. And when their loved ones passed from this life, they continued to live in close physical proximity to their bodily remains.

Family beneath the floorboards

In American society, we spend our lives running away from death. Those who can afford it pay for wrinkle creams, botox, cosmetic surgeries and other means of hiding mortality. Popular culture prefers to keep the elderly out of sight and out of mind. When our loved ones die, we grieve and do our best to move on.

But what if we, like the residents of Çatalhöyük, buried our family members underneath the floorboards of our homes? They would continue to be with us in a very real sense, and we might have to radically reorient our posture towards life and death, knowing that we, too, will reside under those same floorboards someday.

Even stranger, from our vantage point, was their propensity to dig up the dead after many years, remove the skull, plaster and paint it, and circulate it among themselves.

Primary burial of an old adult female with plastered skull (reconstruction by Kathryn Killackey; source: Çatalhöyük Research Project).

This practice was not limited to Çatalhöyük, but is found elsewhere in the Ancient Near East. Anthropologist Ian Kuijt has proposed that these activities represented a two-stage cycle of death ritual. First, they buried immediate family members in an intimate, familiar place. Second, many decades later, the skull removal and adornment signified the deceased becoming “ancestors” of the broader community.

Lest we think of keeping human skulls in our homes utterly alien, Trevor Watkins suggests, “Think of these relics like pictures of deceased parents and grandparents around the house. We make photo albums and scrapbooks as a way to preserve our memories. They provide a shared sense of identity and continuity.”

Clearly there is evidence of strong bonds between the living and the dead. What about the relationships between members of the community themselves?

Hodder’s research team examined the teeth and bones of the deceased to better understand the diets of Çatalhöyük. They found no discernable differences in diet between men and women. There were, however, notable differences by age—the older members of the community enjoyed wider, higher-quality diets.

This dietary evidence is one clue that older residents may have had an elevated social status, and as such, played an outsized role in the society as “elders”. In the absence of a centralized, hierarchical political system, elders could have help shaped the social norms and rituals that maintained strong bonds.

The esteem in which aged members of the community were regarded should also prompt us to reconsider our understanding of Çatalhöyük’s art. Our contemporary culture is obsessed with youthful beauty, and our media is saturated with images of people who have been photoshopped and filtered to perfection. But these figurines in Çatalhöyük do not represent young, nubile bodies. And if they don’t represent gods either, could it be possible that people “past their prime” were held in such high esteem that it would inspire the community’s artistic creations?

A road not taken

History is full of failed utopian societies that prove that opting out of the status quo is not a cure-all, but a city like Çatalhöyük is proof that humans have successfully built complex, stable societies in which all its members can actively participate.

“When I look at the world today,” says Ian Hodder, “I see it becoming ever more homogenous as the global economy advances. I’m particularly concerned about our rising inequality, how we treat old people, and how we treat the environment. There are other ways of living that we can learn from. Çatalhöyük shows us that large communities can last for long periods of time without great inequalities, without marginalizing the elderly, and without wrecking their environment.”

Instead of putting all our hopes in unproven new ventures like space colonies, answers to our struggles may lie just beneath the soil, waiting to be unearthed.

Read Part II of the extremely ancient societies series, which focuses on Çatalhöyük.