Without understanding religion, we limit our understanding of history itself. Although religion quietly weaves throughout various exhibits at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, it has only played a supporting role until now. Recognizing the integral part these colorful threads play in the tapestry of American history, the Center for the Understanding of Religion in American History will open a permanent gallery in 2024. “This will be the first space that tries to tell the full story of religion in America,” said Peter Manseau, who is the first curator of religion hired at the National Museum of American History.

The center aspires to create a narrative in which all Americans can see themselves, regardless of their beliefs, as connected to the history of religion in the U.S. “You have so many kids that come through the Smithsonian. We don’t have religion taught in public schools, but it’s a great way for them to see the role of religion and how it’s affected American history,” said Anthea Butler, the Geraldine R. Segal Professor in American Social Thought at the University of Pennsylvania.

Butler along with other historians and religion scholars, offered her expertise and perspective on what will be presented in the new gallery. She mentioned the need for people to reexamine “the ubiquity of how people think of America as just Protestantism. It’s never been that. It’s not just a Puritan or Presbyterian point of view. Often when you take a basic American history course that’s all you really learn.”

“From my perspective there are not a lot of exhibits like this. There are many religiously affiliated museums that tell particular stories about particular traditions. This is a unique attempt to tell the big story of religion in America in all of its diversity,” said Manseau. “That’s what will set it apart from other attempts to portray religious tradition in a particular space. It’s not the story of a particular community. It’s the story of all these communities.”

The 3,500-square-foot gallery based on the ground floor of the museum is still in the architectural planning stages. It will showcase an immersive exhibit, featuring sounds, media, and objects from the Smithsonian’s collections, as well as presenting live experiences for visitors. The gallery is planned for a duration of at least 20 years with the ambition to become a must-see exhibit for tourists visiting the National Mall.

-

National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Funded by the Lilly Endowment and the John Templeton Foundation, the gallery is a culmination of a decade of exploring religion at the National Museum of American History. Additional early funders of the Museum’s religion activities included Goldman Sachs, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Foundation for Religious Literacy. In 2021, the planning resulted in The Center for the Understanding of Religion in American History as a permanently endowed center.

To trial the idea of a fixed gallery, Manseau created two smaller temporary exhibits—the second of which opened on March 18, 2022, after a delay due to the pandemic. The exhibit, “Discovery and Revelation: Religion, Science, and the Making Sense of Things,” drawing from the Smithsonian’s vast collection, enlightens visitors on how two approaches to understanding the world have interacted and influenced each other to shape American life.

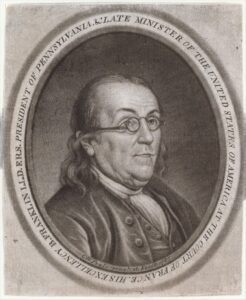

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin’s lighting rod challenged church leader’s beliefs about storms as an expression of God’s vengeance. The script from Apollo 8’s live television broadcast stirred controversy when the crew read from the Bible. A portrait of Henrietta Lacks attempts to capture the religious interpretation her African American family applied to her unjustly acquired cancer cells—studied for their immortal properties—after her death.

The exhibit includes neuroscience’s fascination with religious practice and the mind, including a photo of a Tibetan Buddhist monk wearing electrode sensors during meditation at a lab in Wisconsin. A letter written by Galileo begins a discussion on the impact the Renaissance inventor had on early American thought on science and religion. And, though he never ascribed to a belief in a personal God, the exhibit considers the enduring influence of Albert Einstein’s famous cosmological quips on life and the universe.

“We’re hoping visitors can come away with an understanding that religion and science are two forces in culture that have been mutually influencing each other,” said Manseau. “Many people assume that religion and science are in conflict with each other, but it’s also a far more complicated relationship.”

Manseau hopes visitors come to understand the connection between these subjects in people’s daily lives, informing “how they view the world, the decisions they make, and how we interact with each other.” Both ways of understanding the world provide a means to grapple with the questions: “Where are we in the universe? What does it mean to be human? What do we owe to each other in society?”

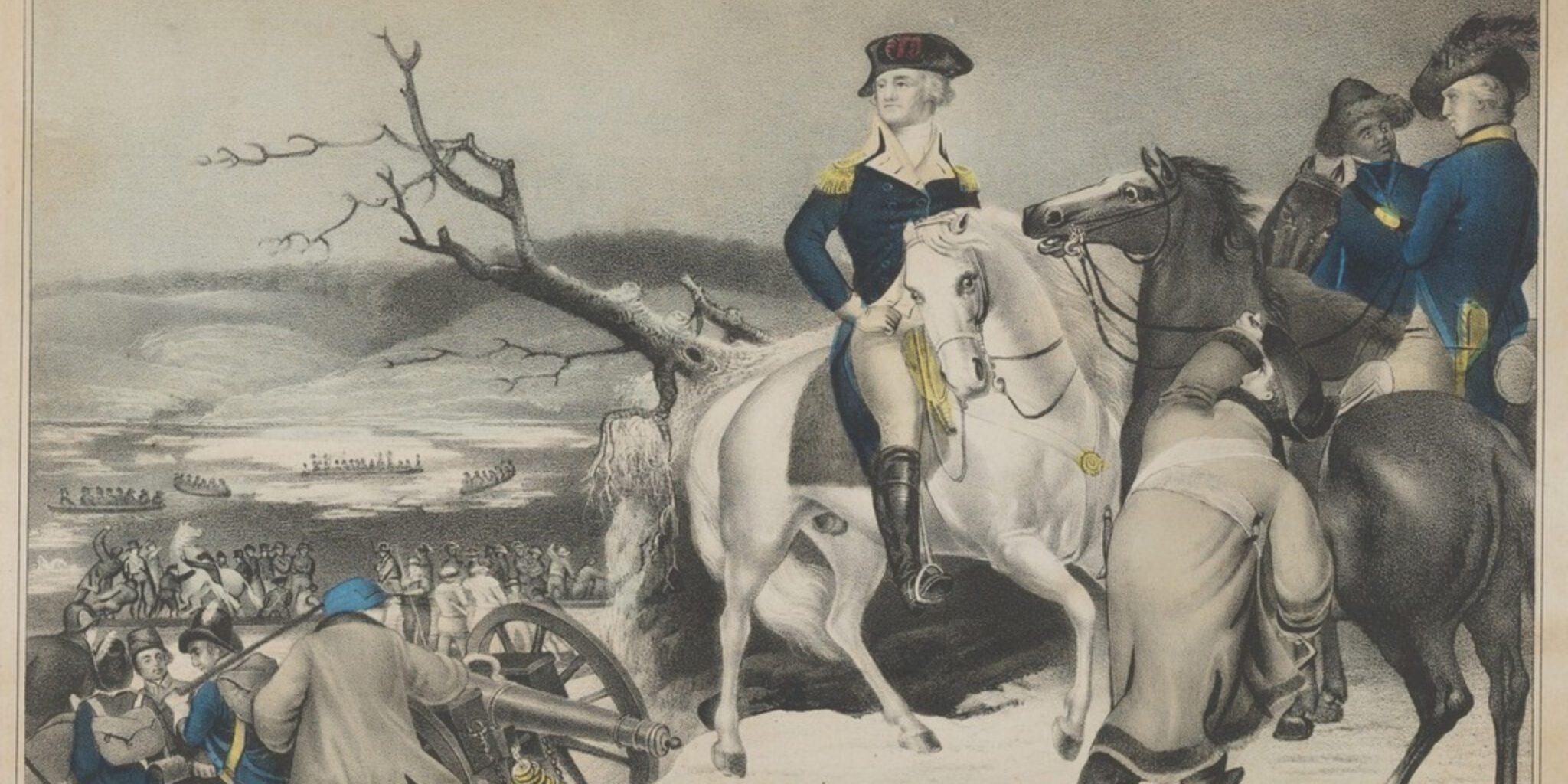

Earlier, Manseau’s first exhibit, “Religion in Early America,” demonstrated how the U.S. has been religiously diverse from its inception. Using about three dozen objects, including George Washington’s christening robe from 1732 and a first edition of the Book of Morman, the exhibit included Protestant denominations, Roman Catholicism, Mormonism, Judaism and Islam, as well as Native American and African beliefs and practices from the colonial period to 1830.

Additionally, the museum presented theatrical performances exploring spiritual traditions and a concert series highlighting religious music, including Wampanoag sacred singing, taiko Buddhist drumming and shape-note singing of Protestant churches.

As these early exhibits and programs showcase, religion is embedded throughout American culture, practiced not only in individual’s private homes or in houses of worship but infusing sports, music, literature, the arts, and influencing commerce and politics.

In an exploratory survey given to visitors to assess their interests, Manseau said that respondents desired more understanding about religious traditions that are not their own, about the diversity of the religious practice in America, and how religion has been a part of the nation’s story from the very beginning.

“We’ve certainly seen through our surveys… visitors don’t want to be told that this is all entirely a happy story of everyone getting along,” said Manseau. “It’s important to tell stories about how religion pulls people together, but also how it pulls people apart.”

The center will tell the complicated stories of how religion has been a catalyst for positive change and as well as an active agent in perpetrating violence. “It’s a story about religion in American that has gone through not just slavery but immigration and all kinds of things that intersect American life,” said Butler. Within that story, the museum wants to explain how religious traditions contain within them a medley of expression and belief—a family not always in harmony.

“You cannot understand American history without understanding religion,”

… said Manseau. “We all need to have a better understanding of where we are coming from… how your neighbor views the world, who we are individually as communities and in relation to each other. It’s a really important part of building common understanding.”

The effort contrasts with many public museums or historical sites, where religion takes a back seat to the main attractions. Yet, as the premier public museum belonging to all US citizens, the National Museum of History is uniquely positioned to narrate stories, like the Jefferson Bible, which Thomas Jefferson self-edited to be in keeping with his own approach to faith.

“They have the means to present a fuller history than other museum-like places are doing,” said Anthea Butler, offering an example. Whereas the Museum of the Bible, a few blocks away, focuses on the global history and impact of a specific sacred text, the Smithsonian is exploring how many different religious traditions have shaped—and been shaped by—various cultural forces, intellectual currents, and pivotal moments in American history.

Butler added that the Smithsonian can also leverage its prestige to receive items on loan from other collections and present them at no cost to visitors. The accessibility of the museum means the Center for the Understanding of Religion in American History can reach the widest audience, bringing together Americans from a diversity of religious backgrounds, including those with none at all.

Rebecca Randall is an independent writer and editor based in the Pacific Northwest. She writes on religion, psychology, the environment, and social issues. She is the former science editor for Christianity Today.