Author’s Note: An earlier version of this piece first took the form of a keynote address to a National Science Foundation conference on the theme of “Art and Science as Parallel and Divergent Ways of Knowing,” which took place in San Francisco in March 2011, though the talk has gone through several widening iterations in the years since, and in turn has been condensed and sampled for its appearance here.

Perhaps, to begin with, a remark by Nabokov—always a good place to start—who at the time was laying out the requisites for being a good novelist, though, for our purposes we might think of these as the requirements for being fully alive. But listen to him closely, because it’s the opposite of how we usually think of these things: “The true master,” he said, “requires, the precision of a poet and the imagination of a scientist. The precision of a poet—and the imagination of a scientist.

-

Vladimir Nabokov, Montreux, October 1969

Keep in mind, of course, that in some precincts, Nabokov was every bit as famous a scientist as he was a writer. A lepidopterist, to be exact, who once surprised his Italian publisher Roberto Calasso by telling him that he’d never been to Venice. “Good Lord,” asked Calasso. “Whyever not?” To which Nabokov answered, self-evidently, “No butterflies.”

Ezra Pound, who liked to insist that poetry should be at least as well written as prose, used to advise young writers (this according to Frank Kermode) “to accept the discipline imposed by Agassiz on his scientific protégés, who had to describe a dead fish over and over till they had it right, as the fish decomposed.”

Or, as Cezanne noted: “You have to hurry if you’re going to see, everything is fast disappearing.”

To return to the subject of poets, though, I often like to start these sorts of talks dipping into poems for what I call the morning prayer. In this instance, two poems. The first coming from Thomas Lynch, the great undertaker poet, the first poem from his 2012 book Walking Papers collection, a poem, as it happens, called “Euclid”:

What sort of morning was Euclid having

when he first considered parallel lines?

Or that business about how things equal to the same thing are equal to each other?

{…..}

how distance

from a center point can be both increased

endlessly and endlessly split—a mystery

whereby the local and the global share

the same vexations and geometry?

Possibly this is where God comes into it,

who breathed the common notion of coincidence

into the brain of that Alexandrian

over breakfast twenty-three centuries back,

who glimpsed for a moment that morning the sense

it all made: life, killing time, the elements,

the dots and lines and angles of connection—

an egg’s shell opened with a spoon, the sun’s

connivance with the moon’s decline, Sophia

the maidservant pouring juice; everything,

everything coincides, the arc of memory,

her fine parabolas, the bend of a bow,

the curve of the earth, the turn in the road.

Sophie the maidservant, as in Sophia, the Hellenistic/Alexandrine personification of Wisdom, although, myself, I like to think of her as pouring milk, and for that matter, to think of Lynch himself having had something quite like Vermeer’s Milkmaid in mind.

Which in turn brings me to a marvelous poem by Wislawa Szymborska, the great Polish Nobel-prize winning poet (as translated in this instance by Stanislaw Baraczak and Clare Cavanaugh):

Maybe all this…

By which she means All This—this hall, those chandeliers, that screen, this podium, me, all of you, this whole building, this city, that bay, the entire surround, all of it…

Maybe all this

is happening in some lab?

Under one lamp by day

and billions by night?

Maybe, Szymborska goes on, we’re all just experimental generations, or there’s no interference, we’re not of that much interest, except for the occasional war or some great migration. On the other hand,

Maybe just the opposite:

They’ve got a taste for trivia up there?

Look! on the big screen a little girl

is sewing a button on her sleeve.

The radar shrieks,

the staff comes at a run.

What a darling little being

with its tiny heart beating inside it!

How sweet, its solemn

threading of the needle!

Someone cries enraptured:

Quick, get the Boss,

tell him he’s got to see this for himself!

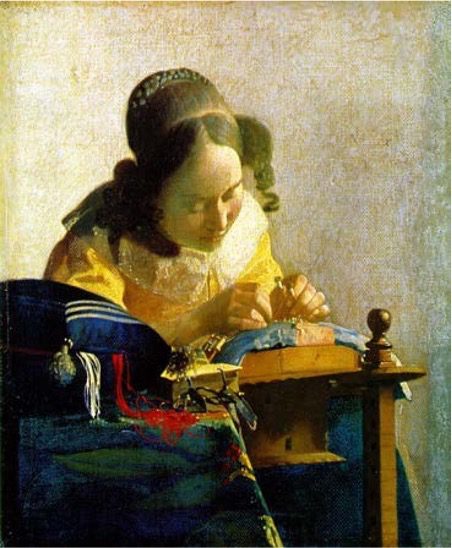

For surely here the image Szymborska must have in mind, the image of the girl spread across the big screen, must be very like Vermeer’s Lacemaker (“In my dreams,” the Polish master had recorded elsewhere, I paint like Vermeer of Delft”).

And one of the most remarkable things about that painting, in turn, is the way that everything in it is slightly out of focus. Either too close or too far, except for the very thing the girl herself is focusing on: The two strands of gossamer-thin thread pulled taught in her hands, the locus of all her labors, that little V of concentration. Indeed, the painting is all about concentration: gradually, in-spiralingly, we come to concentrate on the very thing the girl herself is concentrating on, everything else receding to the periphery of our awareness. Like nothing else so much as a painter—or in this context, we might say, a scientist—lavishing his or her entire attention on his subject. Or else perhaps what happens as we ourselves pause, dumbstruck before this canvas in the midst of our museum walk.

Are we perhaps exaggerating here? Look more closely at the threads themselves:

They arrange themselves, as I say, into that crisp, tight V, couched in the M-like cast of light playing upon the hand and figure behind them. The girl, God-like, momentarily focuses all her attention upon VM: the very author of her existence! And hence back to the poem, for the girl threading her needle, the little darling being with its tiny heart inside, is of course none other than the poet herself, intent over her scribbled page, laboring toward that perfected line—or else subsequently, perhaps us, her readers, hunched over her completed poem. Though, as the creator of the poem, Szymborska is of course also simultaneously the Boss, as we, too, the readers get momentarily to be, recreating, recapitulating her epiphanic insight, seeing it cleanly for ourselves.

Indeed, Szymborska gets it just right. How in the perfected work of art, be it a poem or a painting—or, I would argue, an experiment and its conclusion—across that endlessly extended split-second of concentrated attention, artist and audience alike partake of a doubled awareness: The expansive vantage, lucidly equipoised, of God; The concentrated experience, meltingly empathic, of his most humble subject.

So I want to begin by talking about absorption, about concentration. The moment, as Leo Steinberg says somewhere, “when the artist stops asking, What can I do? and starts asking, What can Art do?” I imagine that’s similar with scientists, too: What is the World doing? Or with Diderot, noting how “painting is best when the artist steps back slack-jawed before his creation”—Diderot, who also said that the artist is merely the first observer of the completed work. Which is to say, that moment when he stops being the creator and suddenly becomes the slack-jawed witness.

Surely, there, too, it must be the same with scientists. I recently read somewhere how Elizabeth Bishop told her first biographer, Anne Stevenson, that she admired “the beautiful solid case being built up out of his ‘heroic observations’ by Charles Darwin,” and went on to say that “what one seems to want in art, in experiencing it, is the same thing that is necessary for its creation: a self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration.”

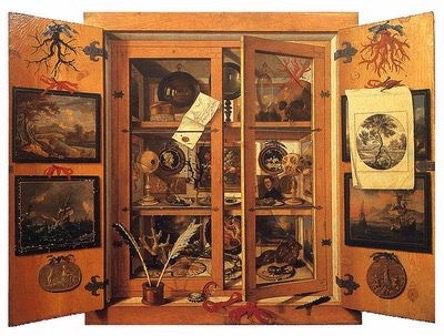

For, of course, the whole distinction between art and science is of relatively recent vintage. Not all that many years ago, in the Age of Wonder of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, aristocrats would vie with one another gathering together wondercabinets, such as this one here,

-

Credit: Lawrence Weschler

more or less following Francis Bacon’s prescription for the essential apparatus of “a compleat learned gentleman,” from 1594, when he said that such a gentleman should attempt “to achieve within a small compass a model of the universal made private.” Any such would-be magus would certainly want to compile, in Bacon’s words, “a goodly huge cabinet, wherein whatsoever the hand of man by exquisite art or engine hath made rare in stuff, form or motion; whatsoever singularity, chance, and the shuffle of things hath produced; whatsoever Nature hath wrought in things that want life and may be kept; shall be sorted and included.” And you’ll notice how in this particular wondercabinet you indeed do have various sorts of scientific apparatus, you have horns and coral and insects, and you have paintings. A good many of the Durers we now come upon at museums began their lives in cabinets such as this, right alongside the shells and the antlers and the skulls. All of them constituting occasions for marvel at the splendors, the richness, the bounty of Creation (the artist’s efforts being merely a token, an instance, a shadow of the greater Creator’s). And all of this occurring under the sign of absorption and concentration— what I call “pillow of air” moments, where suddenly you notice that a pillow of air has gotten lodged in your mouth and you haven’t so much as breathed in ten seconds.

One could likewise cite the examples of Leonardo or Michelangelo, who would never have understood a distinction between their artistic and their scientific practices. After all, the entire field of anatomy, before it split off to become a scientific discipline, was deeply imbricated in artistic practice, culminating of course in the most famous painting of this genre, Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson:

I just want to stop for a few moments to look at this painting which you’ve all seen a thousand times, but perhaps to look at it a bit more carefully. The year is 1632, and this is the anatomy lesson of Professor Nicolaes Tulp, the most eminent anatomist in Amsterdam at the time. Rembrandt in a sense is not yet “Rembrandt,” the one we will come to know and revere over the coming centuries.

He is only 26 years old and has more or less just arrived in town from Leiden; and with this painting, he is effectively putting out his shingle as a portrait painter. In compositional terms, Rembrandt is portraying the professor; a cadaver (who is incidentally a recently executed thief, we even know his name, but that’s another lecture) with his arm flayed (the arm being the member with which he would have stolen the thing for whose theft he had been executed, a cloak not unlike the professor’s very own); and six of the professor’s onlooking students. Granted, the final painting includes seven onlookers, but it’s fairly obvious that that guy over there to the far left came late and demanded to be put in…Or at any rate insisted on inserting himself into the commission at a late stage…Maybe forked over his share of the money late, after everyone else had agreed on the terms of the arrangement…And Rembrandt said,“Okay, you get in, too, but we’ll put you over here.” (And the guy is even portrayed as a sort of clueless doofus.)

The point is the entire composition is a fiction and would have been understood as such by contemporary observers: it is not a snapshot, as it were, intended to be read as the exact recording of a specific moment in time (chemical photography had not yet been invented: nobody could or would even have imagined such a thing). It recalls an event—that day’s anatomy lesson—but everyone would realize that the artist, who was present at the lesson, in addition would have held a series of separate sessions with each of the individual sitters, and then constructed a scene, posing each one in a different posture, frozen with a different aspect (across the length of the actual anatomy lesson itself, of course, each of them would have moved through a whole range of such aspects, Rembrandt would doubtless have sketched all sorts of ideas, but it was only after the fact that he’d have plotted out this particular iteration).

There are all sorts of other things we could say about the cadaver and the way it is portrayed—how the corpse’s presentation, naked except for the sheet covering its midrift, recalls and no doubt intentionally alludes to images of Christ after he’d been deposed from the cross (Mantegna’s and the like)—Christ who after all had himself been crucified, flanked by a pair of common thieves.

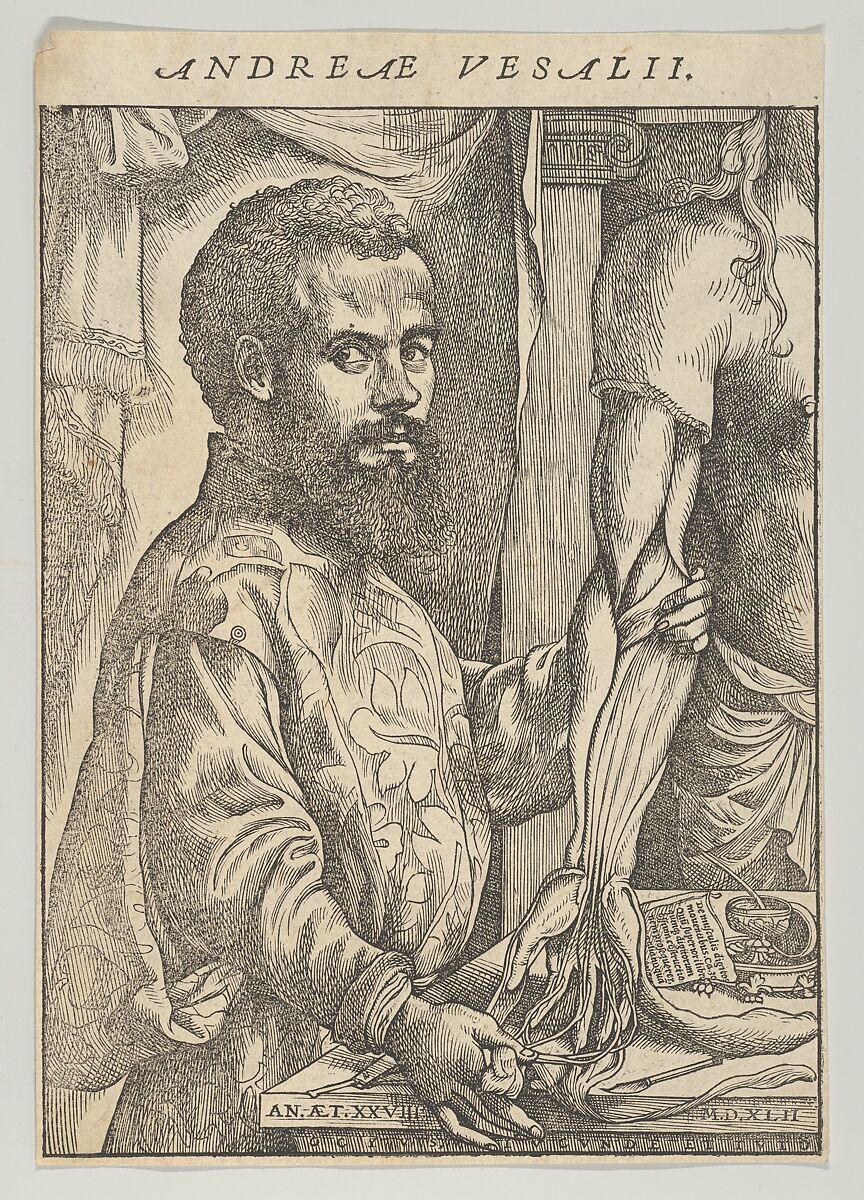

Or about the flayed arm, which is unusual, since in virtually every other anatomy lesson painting or engraving from the period (and there is a whole genre of such images), the part of the body that is portrayed as having been opened out is the part that in fact always was the section first opened in such procedures, which is to say, the belly, the bowels: the part that needed most immediately to be addressed since it would have been the first to start rotting in that era before refrigeration. It has been noted that the arm, flayed like that, likely alludes to the portrait which a hundred years earlier the eminent illustrator Jan van Calcar has offered as frontispiece to the great Andreas Vesalius seminal work on human anatomy, De humani corpora fabricus.

(Some commentators suggest that Professor Tulp would have asked to be portrayed in this fashion as a subtle way of identifying himself as the great Vesalius’s true heir, or that Rembrandt might have been currying favor with the Professor or other possible future clients in advancing this sort of suggestion, or else that Rembrandt might have been casting himself as van Calcar’s true heir, van Calcar for his own part having been a student of Titian’s)

But I want to focus on something else for a moment, or more precisely to have you focus on something else. Because let’s try an experiment: everyone, close your eyes. You’ve all seen this picture a hundred times but I’m curious how you remember it. As you will recall, there’s the corpse, the professor, that doofus off to the left (who we will henceforth bracket out of this conversation), and then the six onlookers ranged, as it were, in two groups, an outer trio, and the inner trio. And those three inner students are gazing intently, awestruck, dumbfounded, at something. But at what?

Now, if you’re like me, you will likely recall them gazing at the flayed arm in hushed, almost queasy astonishment. But—now open your eyes again, and you will see that they are not. Nor, incidentally, are they gazing, as countless academic exegeses of this painting have maintained, at the opened book over there way to the right—the book supposedly standing in for the weight of tradition, or the customary protocols of practice, or whatever. A book’s being the sort of thing an academic book writer might indeed like to imagine they were looking at, but it’s obviously not. No, they’re looking at the professor’s hand.

The professor is saying, “With these muscles here—do you want to see something really amazing?—you can do this.” You can rotate your arm in this fashion. And they are looking at that as if they have never seen anything like it. And indeed, never before have they seen it in this way. Actually when you look at the painting closely (as you can the next time you are in The Hague at the Mauritshuis where it resides, a room over from Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl), one of the things that’s really interesting is that the way that guy in the middle, the goateed fellow craning out over the corpse’s head, has one eye looking at the flayed arm and the other looking at the professor’s. And it’s like a movie: up down, up down.

The point, though, is that this is not a painting about death. It’s a painting about life. And specifically about two of the most astonishing aspects of human life: prehensile manipulability and ocular vision: hand and eye. About the ability to move one’s hand and the ability to see. In other words, about painting: the capacities that specifically make painting possible. A point further reinforced when we now look at the other three onlookers, the so-called outliers. For what are they gazing at? At us, yes. Or at the audience, yes—and there was an audience, these dissections often took place before an audience of variously distinguished guests, as we know did this one. But if you think about it, what they are actually looking at (within the fictional terms of this painting) is Rembrandt himself painting: the painter, his canvas perpendicular to the scene so he can take it all in, gazing at them gazing at him, expertly wielding his brush with his arm, by way of the very muscles the professor is describing.

And those onlookers in turn are no less dumbfounded by the miracle of what is transpiring before them. They are, as we say, getting it.

I mention all of this stuff about looking because one of the things that connects art and science—the practice of the artist with the practice of the scientist—is that moment that goes, “Oh, I see.” I get it. That’s what the scientist says when he or she finally figures something out. I see. The veils, we say, fall from their eyes. They are vouched a fresh perspective. (Although it’s worth noting how Isaac Asimov further refines our understanding of the process by noting how “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds a new discovery, is not Eureka but rather, ‘Hunh, that’s funny.’) What scientists are striving after is what artists are doing all the time. David Bohm, the physicist, says that “Physics is a form of insight and hence a form of art.” Einstein always claimed that imagination was more important than knowledge (though Mark Twain had earlier noted that “You can’t depend on your eyes if your imagination is out of focus”). Leonard Shlian has written a book about art and physics in which he charts how, time and again, the artists were out in front of the scientists. For example, Giotto was working on conic sections and ellipses long before Kepler. Or the ways in which Manet and Monet and Cezanne were playing with compressions of time and space—the plasticity of time and space—decades before Einstein.

One last thing about the flayed arm, though, before we move on, because it seems to me—and it has seemed to others—that in addition to all of the above, by way of that hand and arm, Rembrandt is making a conspicuous allusion to Michelangelo, and specifically to the way the newly born Adam reaches out to God with his stretched hand in the famous image in the Sistine Chapel.

Which in turn reminds me of those neurological writers who have pointed out that Michelangelo’s Sistine God, in turn, was enveloped in a surround of cherubs and puffed out drapes that bore a conspicuous likeness to the very brains with which anatomist Michelangelo would have been so familiar:

All of which I only mention because now that we look at his Anatomy Lesson once again, Rembrandt also seems to have included a subliminal allusion to the interior of a human skull in the way he lit the scene in general (the cranial shape of the fade from light to darkness—once again excluding the doofus off to the far left side—such that the professor’s face almost reads as the eye socket, his shoulder as the nasal cleft, the corpse’s legs as the jawbone):

Having said all of that, there’s one other thing that’s important about this specific painting. As I’ve mentioned, such dissections would have taken place in public theaters. Special guests would have been invited to come. And although quite common in Leiden (from where, incidentally, Rembrandt had only just arrived), they were relatively rare in Amsterdam. We even know the date in this particular instance, for it was a fairly unusual occurrence and it was recorded in public records, January 16th, 1632. And it’s almost certain that there in the room—or such at any rate is the contention of W.G. Sebald in the opening chapters of his magisterial The Rings of Saturn—Dr. Tulp’s students would have been gazing out past Rembrandt at, among others, an anatomy-besotted exile, then resident in Amsterdam, named Rene Descartes.

Sebald convincingly argues that Descartes would not have dreamed of missing the event. And Descartes is important because, only a few years later, in 1637, he would be publishing both his Discourse on Method and his Geometry, with The Meditations on First Philosophy coming only a few years after that, in 1641. And that body of work constitutes, arguably, one of the places where you begin to see the break, the delamination, between the humanities and the sciences, as modernly understood. Not only by way of the mind body/split that comes with Descartes’s dualistic conception (the body no longer conceived of as seat of the soul but rather almost as a robotic automaton, and subject to study as such): “I regard the body as a machine, so built, put together of bone nerve muscle vein blood and skin, that still although it had no mind it would not fail to move in all the same ways as at present, since it does not move by direction of its will or mind but only by arrangement of its organs” (exactly the sort of thing Tulp had been demonstrating with the muscles in the flayed arm). But also with his analytic geometry, with its seminal crucifoid grid of X and Y axes, which would come to allow for the quantitative analysis of all sorts of properties which were once deemed exclusively qualitative. And indeed, you begin to have this split in ways of knowing which will get wider and wider as the years go by, with calculus itself being invented (or discovered) virtually simultaneously by Newton and Leibnitz, only a few decades after that, in the 1680s.

Oliver Sacks, once discussing this moment in European intellectual history in a lecture evocatively titled “The Neurology of the Soul,” concluded by insisting:

“The Cartesian notion of man as a machine is tremendously powerful, and indeed was absolutely necessary for the rise of an empirical, objective science.

But it is not enough.

It cannot tell us about the personal, the “I,” inside the physiological.

A purely physiological explanation offends common sense and one’s own egotism. Mechanistic neurology needs to be complemented by an existential neurology—of face, internal landscape, Individual.

Until we achieve such a conjunction, we can never hope to fathom the mysteries of perception and action but will remain lost in the empty labyrinths of empiricism.

We need, if it’s not a contradiction in terms, a science of the individual, or at very least one that does not do violence to the individual.”

-

Nicholas of Cusa

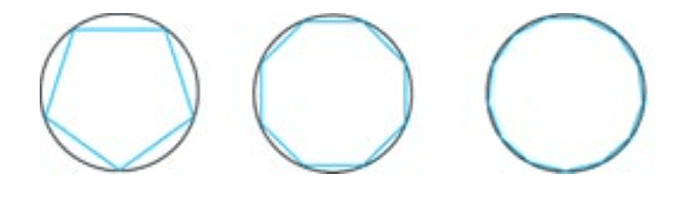

All of which (but especially the discovery of the calculus) puts me in mind of one of my favorite formulations—people who know me get bored with it, but I can’t help but share it with you here in this context. One of my all-time favorite metaphors was provided by Nicholas of Cusa (1401-64) who was a late medieval jurist, astronomer, diplomat, the archbishop of Cologne, and a mathematician, and in that final capacity something of a number mystic. His great masterpiece in that latter regard was called Learned Ignorance (scientists, take note: Einstein would have savored such a title, perhaps he did). At any rate, at one point Nicholas, a good neoplatonist, was engaged in a sort of argument with Aquinas (from over a century earlier) and his followers about ways of getting to knowledge of the whole, which was to say, in those days, knowledge of God. Aquinas, a good Aristotelian, seemed to take the position (granted we are way oversimplifying here) that if you just catalogued everything—if you composed a book on botany, a book on zoology, a book on ethics, on astronomy, and so forth, which is to say to the extent that you were able to, you endeavored to catalog all of Creation—you would eventually achieve knowledge of God the Creator. But Nicholas, for his part, suggested that surely it couldn’t be quite like that. Imagine, he challenged his readers, a circle with an n-sided regular polygon inside. Say, an equilateral triangle. Add a side and you get a square. Add another side and you get a pentagon. Keep adding sides and eventually you get a million-sided polygon.

Granted, at some point it starts looking more and more like its surrounding circle—here he was anticipating the calculus by over two centuries. But in a profound sense, Nicholas went on to argue, the compounding figure in question would have been getting less and less like a circle. For that thing has a million sides, whereas a circle has only one. That thing has a million angles, and a circle has none. At some point, he argued, you were going to have to make a leap—and he coined the phrase, the leap of faith, from the chord to the arc—a leap which in turn could only be accomplished in grace, for free. And those would constitute two essentially different ways of knowing. I’ve always liked that formulation as a writer. You keep piling on detail after detail, and somehow the thing just doesn’t come together, which you can tell, because when you tap it, it just doesn’t ring true. But then suddenly, almost unaccountably, it pops into shape. There’s all that work, which was preparation, preparation as it were for receptivity, but when things finally come together they seem to come together of their own accord. I wonder how much that too is like the work, the practice, of science.

The digital maven Jaron Lanier once wrote about the way that “Information systems need to have information in order to run. But information under-represents reality. What makes something fully real is that it’s impossible to fully represent it to completion” (going on to elaborate: “A digital image of a painting is forever a re-presentation, not a real thing. A real painting is a bottomless mystery, like any other real thing. An oil painting changes over time; cracks appear on its face. It has texture, odor, and a sense of presence and history.”) Such that again we’re back with Nicholas of Cusa: Information is the million-sided polygon, whereas The Real is the circle. Or with Eudora Welty: “Making reality real is art’s responsibility.” Kant says somewhere that a work of art is a specific instance of a general law that cannot be stated.

The late Freeman Dyson, writing in The New York Review of Books, once argued that “The public has a distorted view of science because children are taught in school, falsely, that science is a collection of firmly established truths. In fact, science is not a collection of truths. It is a continuing exploration of mysteries.”

Coming from the other side, James Baldwin once wrote, “The purpose of art is to lay bare the questions that have been occluded by the answers.”

In closing I’d like to evoke a few last thoughts from other people. One of my favorite writers is The New Yorker’s Ian Frazier. He once had a wonderful piece in the magazine which was called “Bear News,” one of those pieces which only goes to show that a real writer can make a marvelous piece out of just about anything. In this case, he had been collecting clippings of bear-human encounters, and he eventually decided to inventory the results, concluding finally as to how:

“It’s possible to walk for a long time through the woods and not see much of anything. Beautiful scenery makes its point quickly; then you have to pay attention or it starts to slide by like the looped background in a Saturday-morning cartoon. A pinecone falls from one limb to another, a rock clatters down a canyon, and your own thoughts talk on inside your head. People sometimes say that what is great about bears, and especially grizzlies, is the large tracks of wilderness that they imply—that a good bear population implies a healthy, unspoiled habitat. But bears don’t simply imply wilderness—bears are wilderness. Bears are what all the trees and rocks and meadows and mountains and drainages must add up to. When you see a bear, the spot where you saw it becomes instantly different from every place you’ve seen. Bears make you pay attention. They keep the mountains from turning to a blur, and they stop yourself from bullying you like nothing else in nature. A woods with a bear in it is real to a man walking through it in a way that a woods with no bear in it is not. Roscoe Black {—and how I love that name, it’s perfect in this context!—}, a man who survived a grizzly attack in Glacier Park several years ago, described the moment when the bear had him on the ground. ‘He laid on me for a few seconds, not doing anything…. I could feel his heart beating against my heart.’ The idea of that heart beating some place just the other side of ours is what makes people read about bears and tell stories about bears and argue about bears and theorize about bears and dream about bears. Bears are one of the places in the world where the big mysteries run close to the surface.”

I began with some poems and I think I’ll end with a poem as well. This one is from Tomas Transtromer, the great, great Swedish poet. (In the old days I used to say how if there were any justice in the world he would have been awarded the Nobel Prize a long time ago, but unfortunately the Nobel Prize was given by Swedes and they appeared to be too shy and self-effacing to give one to one of their own—but then, in 2011, they went and proved me wrong, properly honoring him after all.)

At any rate, he had a great poem called “Sentry Duty,” here translated by Robert Bly. Apparently in Sweden they have, or used to have, some form of universal conscription; everyone had to serve in the army for a year or something like that, to guard the Finnish border, or some such. And this is a poem about one of the nights, back in his younger days, when he’d been staked out, doing just that.

I’m ordered out to a big hump of stones

as if I were an aristocratic corpse from the Iron Age.

The rest are still back in the tent sleeping,

stretched out like spokes in a wheel.

For his own part, Transtromer goes on to suggest, how out there in the cold his mind drifts back to other climes, summer afternoons with a girlfriend…

I brush along the side of {such warmer} moments

but I can’t stay there long.

I’m whistled back though space—

I crawl among the stones. Back to here and now.

Task: to be where I am.

Even in this solemn and absurd

role, I am still the place

where creation does some work on itself.

{…}

But to be where I am … and to wait.

I am full of anxiety, obstinate, confused.

Things not yet happened are already here!

I feel that. They’re just out there:

a murmuring mass outside the barrier.

They can only slip in one by one.

They want to slip in. Why? They do

one by one. I am the turnstile.

To be the turnstile, and to wait. To be the place where Creation gets to do a little work on itself. One could hardly do better by way of characterization of the scientist’s lot, and the artist’s. Only attend.

Lawrence Weschler, director emeritus of the NY Institute for the Humanities at NYU, is the author of over twenty books, including And How Are You, Doctor Sacks? a biographical memoir of his thirty-five year friendship with the neurologist. These days, he curates Wondercabinet, a Substack fortnightly of the Miscellaneous Diverse, which focuses in part on the overlaps between art and science.