Scientists’ curiosity about natural phenomena – rocks or bugs or stars – or the marvels of technology often begin in childhood. Their biographies are filled with passages like this:

“Somehow, it was quite obvious to me what [the telescope] was for, and I was soon using it to observe the bustling life of [my] town, especially the marketplaces…. Later I used the telescope to peer into the night sky… which offers, in the high altitude of [my childhood home], one of the most spectacular views of the stars.”

The moon and a pocket watch also fascinated this young boy. Yet, professional science was not a career option for him. He is today among the most revered religious leaders of our age: His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. But as a boy, he preferred the marvels of science and technology to his study of philosophy and Buddhist texts.

His fascination with the natural world and how objects of a technological culture worked led him to innovate the way Tibetan monks and nuns are educated.

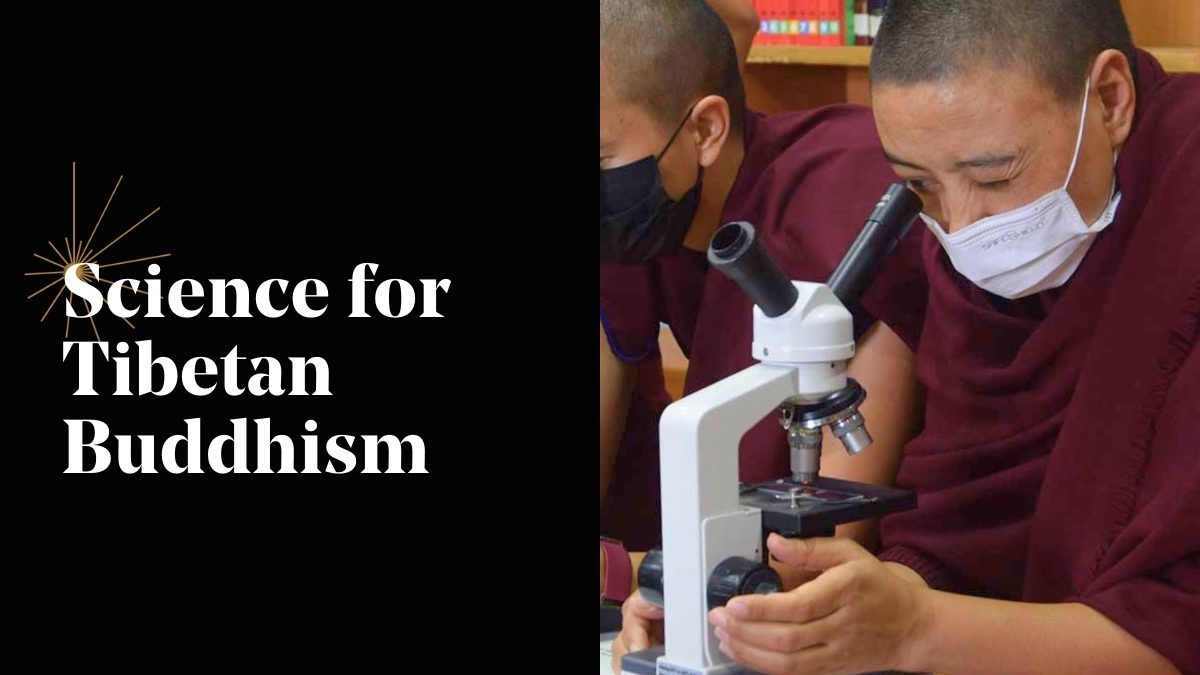

Today, Tibetan monastic students peer into telescopes and microscopes and marvel at the way nature works, whether within our bodies and minds or throughout our galaxy. Through key partners like Science for Monks & Nuns and the Emory Tibet Science Initiative, the Dalai Lama has given all those called to a monastic lifestyle the opportunity to share his boyhood passion. Their engagement with science is now influencing traditional Buddhist learning as well as the wider Tibetan community.

A role for science in spiritual formation

Beginning around 1987, the Dalai Lama started regular meetings with scientists. He was fascinated to learn neuroscience and physics, often stunning the scientists with his thoughtful questions. From early on, he thought that science should be part of the formation of Tibetan monks and nuns. He knew change in how monastics were trained could change the world, but that such change would be hard and take time.

Beginning around 1987, the Dalai Lama started regular meetings with scientists. He was fascinated to learn neuroscience and physics, often stunning the scientists with his thoughtful questions. From early on, he thought that science should be part of the formation of Tibetan monks and nuns. He knew change in how monastics were trained could change the world, but that such change would be hard and take time.

The Gelug monastic program he wanted to change was more or less the same as it had been when its founder Je Tsongkhapa established the order in 1409. According to Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi, the man the Dalai Lama tasked with implementing this change, the monastic leaders were reluctant at first “because of their limited knowledge about what science is and what this new education entails.” Moreover, “they feared that bringing something new might distract the monastic students away from traditional studies and thus undermine the curriculum that had been practiced, preserved and promoted for more than 600 years.”

Scientific training for monks

In 1999, His Holiness instructed the director of the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives to launch a science initiative in three of their main monasteries, Gaden, Drepung, and Sera Jey. The first four-week workshop introduced science to 50 monk scholars in 2000, and a year later, the program scaled up and became Science for Monks. By 2008, Science for Monks expanded to include a leadership training program for local residents to carry out science instruction themselves. Since their start, over 1,000 monks and nuns have begun to teach science and conduct research.

These efforts paved the way for programs like the Emory Tibet Science Initiative (ETSI) and the formation of new centers as central hubs at specific monasteries and nunneries for science-engaged activities and public outreach. In recent years, thousands of Tibetan youth have explored connections between science and Buddhism and discovered how Buddhist learning is relevant to contemporary life and thought.

Groundbreaking institutional change in monastic education

A key step in the process occurred in 2013 when key leaders of the Gelug order, the predominant school of Buddhism practiced in Tibet, passed a historic resolution to add science education within their core curriculum. One year later, eight of their monasteries experimented with the initial science curriculum, with several other monasteries and nunneries following soon thereafter.

Today, ETSI is wrapping up this decade-long experiment of implementing a wide-ranging, 6-year course of scientific study for students. Nearly 1,500 monks have already completed coursework in physics, biology, neuroscience, and the philosophy of science and nearly 2,000 monks and nuns are currently enrolled in the program. Collectively, they represent 14 monastic institutions, largely at universities in Karnataka, India because of the Dalai Lama’s exile from the Tibetans’ historic homeland, which lies within the People’s Republic of China.

The language of change

The first big hurdle for teaching science to Tibetan monastics was translation. Contemporary science operates mostly in mathematics and the English language. Neither was well known to the monastics. So the change required a massive translation effort.

Each year since 2009, about 500 new scientific terms have been added to the Tibetan language. “Lte-rdhul” for the nucleus of the atom; “Dbang-rtsa phra-gzugs” for neuron; and “Kham-tsig klad-zho” for the amygdala. “Kham-tsig” is an almond but adding “klad-zho” suggests the amygdala is an almond of brain substance.

This process, which led to 5222 science terms in the first edition of the English-Tibetan Modern Science Dictionary, is part of what Emory University biologist Arri Eisen considers to be a major experiment in its own right. It is testing what changes can occur at the interface of science and Buddhism, with scientists like Eisen teaching science to Tibetan monks and nuns; and those monastics in turn teaching the scientists about Buddhism.

Science is known for progress and change; religion is less so. Change within a religion is often a process of translation; making the key tenets of the tradition known to new audiences. For ETSI, the first task was to make the key ideas of science known to the monks and nuns. Without over 5,000 new science terms in the Tibetan language, change to the 600 year-old Gelug monastic program could never have happened.

A give and take between students and teachers

“Do bacteria require light?” asked Tashi, one of Eisen’s maroon-robed monastic students. Eisen had spent the week teaching monks and nuns cellular and molecular biology using a question of interest to Buddhists: can bacteria sense? If they can and if bacteria are sentient beings, then, according to Buddhism, they would be reincarnated beings and should not be killed.

Eisen gave the scientific answer to Tashi’s question – “Some bacteria require light and use it to make energy via photosynthesis” – and learned later that Tashi’s question was not primarily scientific. It was motivated by the Buddhist view that light is related to consciousness. Tashi’s question was to understand if bacteria could be conscious.

Eisen is one of over 200 Western scientists representing 109 academic institutions involved in ETSI. But this experiment with Western science and Eastern religion was never a one-way exchange. Western scientists have learned to appreciate the Buddhist empirical approach. Monastics are trained to be skeptics and to only accept ideas after a careful review of the evidence. From his 30-year dialogue with science, the Dalai Lama famously said, “If science proved some belief of Buddhism wrong, then Buddhism will have to change [that belief].”

This shared empirical approach is leading to advances in science, too. Psychologists have found that exposure to Buddhist concepts reduces prejudice and increases prosociality. Meditation research, rooted in Buddhist practices, has shown benefits to immune system functioning, how it calms the mind producing emotional balance that can reduce anxiety and depression, and can even slow the rate of brain atrophy.

Eisen notes that scientists participating in this program often change the way they approach their research. “One hardcore scientific reductionist studying computation neuroscience, after teaching the monastics for several years entirely reframed and rethought his research in terms of the nature of freewill.”

Northwestern University neuroscientist, Robin Nusslock, sees value for science in the Buddhist spiritual ideal of compassion. “Science would benefit from being guided by the principle of compassion, and a commitment to enhance the welfare and well-being of all sentient beings. Scientists can learn a lot from Tibetan Buddhism in the pursuit of this ideal.”

Photos from Science for Monks & Nuns Institute IV- Neuroscience Workshop (March 12-30, 2023)

Pursuing long-term sustainability

As the ETSI program pursues sustainability, Eisen and his colleagues will be less involved in the teaching. That responsibility will largely fall on the 37 monks and nuns who have completed a two-year, science-intensive program at Emory over the past decade. These “Emory monks”, formally known as Tenzin Gyatso Science Scholars, share an off-campus apartment in Atlanta, take undergrad science classes with Emory students, and rely on Facebook and other social media to communicate with family back home as they navigate the hectic existence of American college life. Other monks and nuns currently completing special trainings in India will be joining them as long-term faculty for the monastic science curriculum.

Lodoe Sangpo, a monk from the first cohort of Tenzin Gyatso Science Scholars, understands the task they face as Tibetan science instructors. “We have a huge responsibility.” Sangpo and his peer instructors had to learn math and basic science on their own before launching into college level biology, chemistry, physics, and neuroscience. Now they must teach those basics to future generations of Tibetan monastics.

Over the past four years, Sangpo has not only been teaching science at Gaden Jangste Monastery, but has also participated in mediation research with American and Russian scientists. He was co-author of a peer-reviewed article for the International Journal of Psychophysiology.

To support native Tibetan science teachers like Sangpo, several of the largest monastic universities now have science centers with basic resources and materials so they can properly teach science. Much of this is having the technology to access recorded lectures and supporting texts as well as the basic equipment necessary to demonstrate scientific concepts and undertake simple laboratory tasks.

What do those demonstrations look like? When a monastic student asks his physics instructor how sound travels without particles moving from one place to another, she lines up 5 monks to demonstrate. The first gently pushes the second, the second pushes the third, and so on down the line, each returning to their original position after they shove their neighbor. The curriculum favors this kind of experiential learning. The monks take great delight in this particular demonstration, asking to see how sound propagates along the line of their peers one more time (watch below beginning at minute 52).

Testing Templeton’s Vision

Sir John Templeton was curious to know if learning science could enrich our great spiritual traditions; and in return, if humanity’s great spiritual traditions could positively contribute to science. This unique experiment within Tibetan Buddhism is precisely the kind of philanthropic investment he wanted to make.

Since 2011, Sir John’s foundations have invested $9 million in ETSI and Science for Monks & Nuns, helping produce a robust science curriculum, supported by international networks of teachers, with the pedagogy, materials, and thousands of new scientific terms in the Tibetan language to ensure conceptual clarity across the participating monasteries and nunneries. Now we wait to see what happens when Tibetan monastics learn about “almonds of brain substance” and Western scientists engage the contemplative traditions of Buddhism.

Negi sees progress. “Thanks to more than a decade of education, the monastics’ attitude toward science education has changed and is changing, especially amongst the younger monastics.” However, he admits there is lots of work to be done as “the buy-in from the Tibetan Buddhist world is still limited,” especially outside of the Gelug order.

“The extraordinary forward-thinking vision of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, which I see as closely aligned with Sir John Templeton’s, is grounded in a call for a spiritual revolution, and more recently a compassion revolution, that is very much needed in our times.” According to Negi, “This bringing together of two cultures – scientific and contemplative – is not a short-term project. For science to truly become part of contemplative communities, and for contemplative practice to become mainstream among scientific communities – this is more like a hundred-year project.”

Ven. Lobsang Pelmo, one of the first nuns trained at Emory, has seen the interest of the nuns at Jangchup Choeling Nunnery in the intersection, even the integration, between modern science and Buddhism. She is hopeful this modification in how she and her peers are educated can change the world. “I deeply believe that it can help create a better world – promoting exchanges of knowledge, collaboration and cooperation.”

Science in the Future of Tibetan Buddhism

At the onset of this initiative, in 2000, His Holiness the Dalai Lama remarked, “Our community shall not remain as it is. There will be changes… The knowledge of science will be instrumental in the preservation, promotion and introduction of Buddhism to the new generation of Tibetans. Hence, it is very necessary to begin the study of science.”

Nearly 20 years later, due in large part to the suite of partners and activities pursued by Science for Monks & Nuns and the Emory Tibet Science Initiative, that vision is being realized. The boy fascinated by the inner workings of a watch and the shadows on the moon is seeing real change because of Tibetan Buddhism’s engagement with science.