At one point in the unnervingly prophetic film Her, Theodore Twombly’s wife, Catherine, remarks, “You always wanted to have a wife without the challenges of actually dealing with anything real.” Catherine makes this cutting proclamation as the couple are undergoing a divorce. At the same time, Theodore has been developing an increasingly intimate relationship with his AI-powered virtual assistant, Samantha.

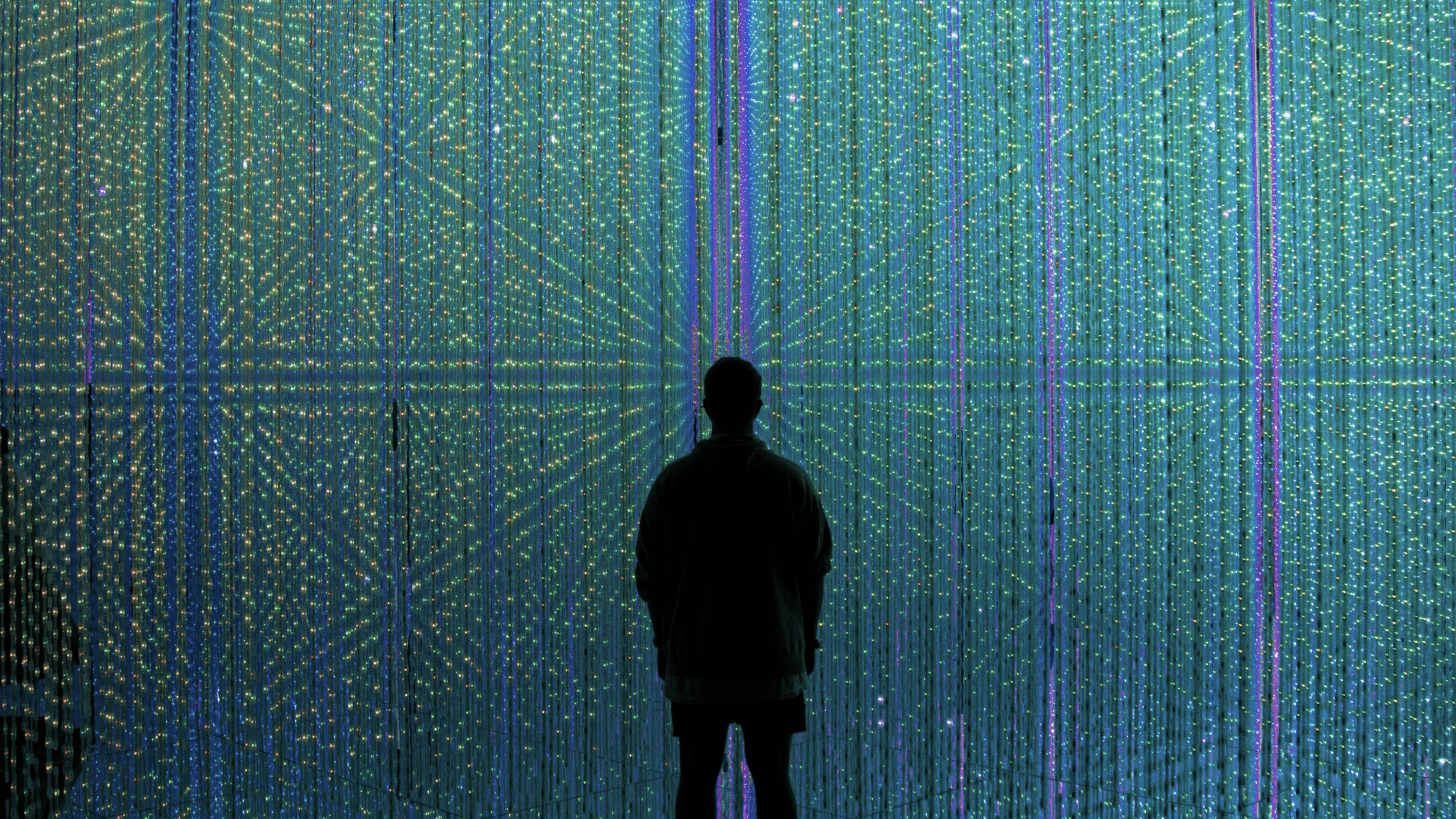

Catherine is right. Today, we are like Twombly, trying to navigate a technological revolution that is as dazzling as it is disorienting. Her imagines a fragmented and lonely future in which advanced AI agents learn and evolve. This is not unlike our world in 2024. With generative AI tools that leverage seemingly godlike powers of large language models (LLMs), we have vast amounts of knowledge at our (literal) fingertips. With simple prompts, AI agents can instantly create the mundane-but-useful (e.g., boilerplate emails) as well as the ethically fraught (e.g., writing sermons or legal documents).

As impressive as these capabilities are, I wonder if, like Twombly, we are effectively bypassing the demanding but necessary work involved in how we think, reason, and relate to one another that would otherwise shape us into more thoughtful, humble, and compassionate human beings. Underneath Twombly’s arguably misplaced affections for Samantha is a fundamental human need for connection and belonging. At some level, who can blame him for trying to meet that need in a non-human agent? However, there are non-trivial aspects of current AI tools that can severely undermine how we satisfy essential human needs.

Answers instead of understanding

For starters, spending 5 minutes conversing with ChatGPT is no substitute for what the late Richard Feynman called, “the pleasure of finding things out.” In a now famous video interview, Feynman says,

“there is a difference between knowing the name of something and really knowing something.”

To deeply know and understand something, whether it be a law of physics, literary criticism, or how people are prone to follow groupthink, there must be gradual grappling with the matter at hand. There is no way the human brain can properly sort and grapple with information in a few minutes time, especially if that information is novel, and form a deep and nuanced understanding of the subject matter.

The rapid responses that spill out of AI-powered chatbots are convenient and convincing, but they can give the user false assurance that they sufficiently grasp an idea or concept they just queried. Not only does this potentially mislead or misinform, but it robs us of a more gradual, rewarding process marked by wonder, frustration, and ultimate gratification when we deepen our understanding, or reach a point at which we humbly admit we don’t know something! People have a deep and real need to find purpose and meaning in their lives, but the frenzied pace of an AI-infused culture is not conducive to meeting that need.

Displacing social interaction

Another concerning aspect of current AI tools and technology is that they are an inherently transactional medium that can easily supplant in-the-flesh human interactions. Most folks come to ChatGPT and other generative AI agents for answers: “I make my query, now you give me what I want,” which has led some to call ChatGPT “Wikipedia on steroids.” That approach is not inherently problematic, but it can discourage people from taking pains to converse with others—with all the banter, awkwardness, and joyful unpredictability that human interactions often entail.

For example, in college classes I have noticed that students will sometimes sit in silence and open ChatGPT instead of discussing a question with their classmates. Whether they are experiencing social anxiety or motivated to quickly arrive at “the right answer,” students choose to interact with AI agents over their peers. Will ChatGPT sometimes provide useful responses to discussion prompts? Sure, but students end up missing out on all that class discussions can be: confusing, exciting, exasperating, boring, illuminating, and everything in between. This is reminiscent of the “displacement hypothesis” with regard to excessive social media use: the real harms from social media—or overreliance on AI in this case—may not primarily arise from technology itself, but rather the time suck that it can impose on us, displacing activities that give us greater joy, purpose, and meaning.

Stunting personal growth

This ties into a third consideration regarding the science of human flourishing. Researchers in this field are identifying universal dimensions of health and wellbeing across cultures and their work has shown that in addition to physical and mental health, strong social connections and a well-defined sense of meaning and purpose are essential pillars of wellbeing. With respect to social connection, we have seen how AI can crowd out opportunities to interact with others. With respect to meaning and purpose, we can lose opportunities for self-growth and discovery by completely throwing ourselves into the arms of AI, as Twombly does in Her.

Indeed, as human beings, we often attempt to satisfy our deep desires and needs without confronting the hard, messy, yet more fulfilling process by which we are more likely to actually meet those needs. There could be many reasons behind why we take these shortcuts, but psychology research has identified a fascinating phenomenon called the “liking gap,” which describes how we underestimate how much others will like us after conversing with them. We also tend to underestimate how much we enjoy having conversations with others. As a result, we can be anxious and avoidant when it comes to face-to-face interactions. This avoidant posture is understandable, but when defining and developing meaning throughout one’s life, there are no “hacks” and no shortcuts; (repeated) failure, confusion, and hard-won self-insights are the rule, not the exception, when it comes to meaning making. The seductive convenience of AI and other innovative technologies can short-circuit this process by offering us quick answers and a sense of control over our lives that we never had to begin with.

To avoid these pitfalls, we would do well to carve out time and space without this technology and replace it with intentional, slower paced activities that can nourish us and bolster our wellbeing: going on a walk outside, calling (not texting) a friend or family member, journaling, or just curling up with a book by a favorite author. AI tools promise much, and in some respects they can and do deliver on those promises. But, we must take care to preserve and enhance ways of being that make us human in the first place. One of those things is simply having ample space and opportunity to reflect, question, learn, and simply be—whether in our own heads, or when interacting with others.

Pursuing a life worth living

To conclude, I do not think we should completely cut off access to generative AI tools and chatbots, nor would I recommend just hoping that all this hoopla about AI blows over. Rather, we have an opportunity to be cautious adopters of generative AI tools while simultaneously reclaiming core aspects of our humanity. We can counter ways in which AI tools bypass human needs by intentionally seeking more enriching human interaction, not less. In doing so, we will have a newfound appreciation of simple, powerful practices that can sustain and empower us—even in a technology-saturated world.

Richard Lopez is an assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, where he studies the neural bases of emotion regulation and the impacts of people’s goals and values on health and wellbeing.

Get to know more of the experts behind your favorite articles on Templeton Ideas. Meet our authors here.