Carol Adelman and the Hudson Institute adapted an established business ranking method to assess philanthropic freedom worldwide.

Every year, the World Bank publishes a “Doing Business” index that ranks how easy it is to start and maintain a business in 190 countries. (New Zealand has held the top spot for years.) But non-profit ventures are just as globally widespread as for-profit businesses, and just as subject to red tape, government restrictions, and potential corruption. In an era of “venture philanthropy,” which applies startup-like standards of innovation and efficiency to non-profit work, the global context matters even more.

Every year, the World Bank publishes a “Doing Business” index that ranks how easy it is to start and maintain a business in 190 countries. (New Zealand has held the top spot for years.) But non-profit ventures are just as globally widespread as for-profit businesses, and just as subject to red tape, government restrictions, and potential corruption. In an era of “venture philanthropy,” which applies startup-like standards of innovation and efficiency to non-profit work, the global context matters even more.

And since 2015, the non-profit sector has had its own rigorous index, thanks to the work of teams at the Hudson Institute and the Indiana University School of Philanthropy.

“My question was, who’s measuring global philanthropy?” says Carol Adelman, director of the Center for Global Prosperity at the Hudson Institute, a policy think tank. “The answer was no one.”

So Adelman and her team at the Center created the first in-depth study of the hurdles philanthropic organizations face in 64 countries. In 2015 they published the results of their work, the “Index of Philanthropic Freedom,” following an earlier, successful pilot across 13 countries.

Surveying the Globe

The 64 countries Adelman’s team examined account for 81 percent of the world’s population and 87 percent of global gross domestic product. The Index ranks them based on three factors: the ease of registering a non-governmental organization (NGO), favorability in tax treatment towards civil society organizations (CSOs), and the ease of sending and receiving cash and goods across borders.

The Netherlands took the top spot, thanks to the country’s open philanthropic culture: NGOs can register almost as soon as they get the appropriate paperwork, limitations on transfers across borders are minimal, and nearly anyone can serve as the head of an organization. “As a result,” the report reads, “CSOs in the Netherlands are almost uniquely free of governmental control and involvement.”

By contrast, last-ranking Saudi Arabia’s civil environment is plagued by nepotism, tight capital controls, and the government’s near-absolute authority to dissolve CSOs deemed as perpetrators of public disturbances. A 1990 law “makes it practically impossible to receive donations from abroad,” the report says.

Philanthropy is Political, Not Just Economic

The Index has been so well-received that it has outgrown the Hudson Institute, Adelman says. The Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy now oversees the project, giving institutional weight to the effort to encourage governments to open up their philanthropic environments.

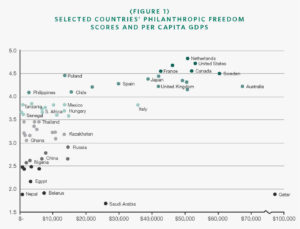

“Countries have said, ‘We can’t have philanthropic freedom because we’re not a rich country,’” Adelman says. But the Index rankings show only weak links to a country’s wealth or development. For example, the Philippines’ philanthropic freedom score (4.1) is more than double Qatar’s score (1.8), although Qatar has the world’s highest per capita GDP — almost 17 times higher than the Philippines. This kind of rankings upset is far more common than in the World Bank’s Doing Business Index, where wealthy countries cluster at the top.

“More than a third of countries with per capita GDP below $25,000 ranked in the top half of the study,” Adelman says.

Those countries especially benefit from an open philanthropic climate. After Typhoon Haiyan struck the Philippines in November 2013, philanthropic organizations poured in money and resources with relative ease, saving countless lives. Whether it’s speedy disaster response or patient, long-term development, the Philanthropic Freedom Index is showing governments, NGOs, and strategically minded philanthropists how to make the most of the world’s willingness to give.