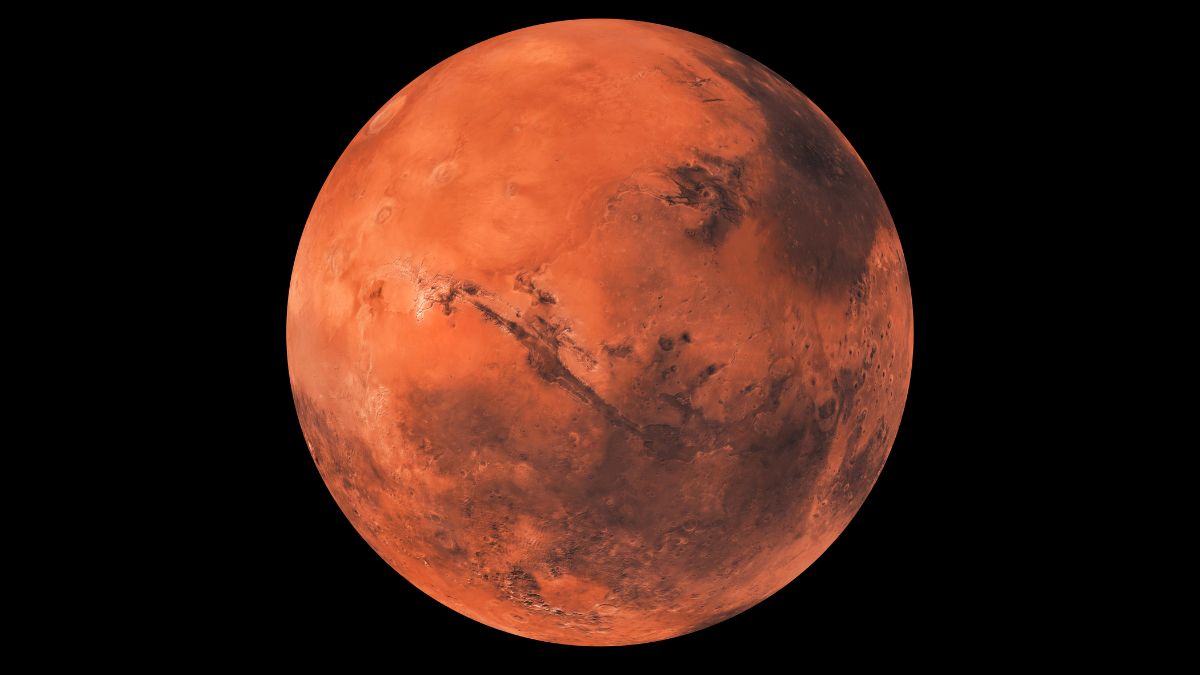

Long before humans began to explore outer space, long before the invention of telescopes, Mars was known as the Red Planet. Even to the naked eye, sunlight that reflects off Mars appears red to humans gazing at the night sky. Why is that?

Relentless human curiosity and centuries of technological innovation have helped us discover that the distinctive color of Mars results from large amounts of iron oxides (rust) present on its surface and in its atmosphere. The minerals of the planet hold the key to its appearance.

Earth, on the other hand, appears primarily blue because oceans cover 70 percent of our planet’s surface. Seen from far, far away, Carl Sagan famously called Earth the “pale blue dot.”

A red Mars and a blue Earth are surely two of the most stable features of our solar system, right? Not so, according to mineralogist Robert Hazen. In this video, he explains that over 4.5 billion years, Earth has taken on strikingly different hues—black, blue, gray, red, white, and green—as major transitions have taken place over immense periods of time.

Even over astronomical distances, we can discern a lot about the characteristics of a planet, and perhaps the presence (or absence) of life, by means of the colors and minerals that we detect.

Some minerals only exist as a result of biological activity. Before life evolved on Earth, there were probably 1000-2000 distinct types of minerals on our planet. Our moon has only 300. Mars has 400-450. But now, as minerals and organisms have co-evolved on Earth, our planet boasts more than 6000 minerals.

“Minerals tell stories because they are incredibly information-rich,” says Hazen. “Every mineral is a time capsule.”

As we study exoplanets throughout our galaxy and beyond, could certain minerals serve as bio-signatures that indicate the presence of life outside our planet? What stories will rocks tell us next?

As one famous playwright put it four centuries ago,

“There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”