It has been said that the twentieth century was the age of physics and the twenty-first will be the age of neuroscience. One way to think about this is that while much of the most celebrated science of the last century was devoted to understanding the movement of bodies in space, from the tiniest subatomic particles to superclusters of galaxies, a good deal of the current century’s science seems set to address the machinations of mind and the attendant complexities of human behavior. Whereas in the twentieth century, physics articulated a picture of the external world with the twin pillars of quantum mechanics and general relativity, in our current era, more and more scientific research aims at describing the inner world of human perception and experience.

Institutes for the study of mind are springing up all over the globe at universities and colleges and at new independent centers. Conferences are being convened; journals are being founded; there is an ever-expanding array of books and articles for both academic contexts and the general public. The John Templeton Foundation has been a significant supporter of more than few of these endeavors.

It’s hard to talk about the twentieth century without talking about physics and the tremendous advances in this field, not only theoretically but also in terms of their impact on our lives. By some estimates, thirty percent of the US economy is based on technologies emanating from quantum mechanics – microchips, computers, cell phones, and anything that incorporates a laser.

Yet there is no doubt the engines of technological change and economic power are shifting. The new ‘new industries’ are not so much about creating novel things as they are about creating new types of experiences. Playing computer games, cohabiting digital environments, participating in online communities, immersing ourselves in virtual worlds – these and other experiential activities are driving much of our economy. The future will be marked by the innovative happenings and encounters available to the human self, both as individuals working and playing on our own, and as members of wider social networks.

The New Sciences of Mind

This is why it seems to me that the ‘sciences of mind’ – including neuroscience, psychology, consciousness studies, psychopharmacology, behavioral economics and the burgeoning array of ‘marketing sciences’ – are the sciences of now. There is a sense in which ‘stuff’ is the past. Stuff is what you get from knowing how to manipulate matter – literally from understanding ‘phys-ics’ in the classical sense of that word – and we’ve become masterful at that. But although there will always be new toys to buy, stuff no longer surprises us and we’ve become anesthetized to the churn of products.

What so many people seem to crave now are experiences of joy or beauty or exhilaration; the challenges of a quest, the thrill of a chase, or the feeling of triumph from overcoming a horde of opponents in computer games. Or a sense of belonging that might be fostered by far-flung communities accessible via a smart-phone or through deeper connections with our real-world neighbors.

Some people want to be taken out of themselves into fantastical virtual worlds where they can experience ‘life’ in a different kind of body, perhaps one that can teleport or fly. Others seek to be more mindful and present in the now, using psychological and mindfulness practices, often coupled with virtual tools, to try to ground their psyches and still their minds.

Both camps share a desire for engagement of the ‘self,’ that ineffable quality which feels so real yet has been so hard to account for within the framework of science so far.

Where does the ‘self’ – the phenomenon we refer to every time we utter the infra-thin but monumental word ‘I’ – fit into the world picture described by modern physics? In truth it doesn’t. And in part, the emergence of ‘mind sciences’ can be seen as an attempt to rectify this omission. If stuff was at the center of scientific attention in the past, a major focus for science in the foreseeable relates to the study of self.

Self and Space

The occlusion of self from the domain of physics was actually part of the plan, and how this central aspect of our being got excluded from the modern scientific description of the world is a part of the history of science worthy of closer attention.

In this essay I want to propose that concepts of self and concepts of space are inextricably entwined so when a society develops a new conception of space – as the founders of the scientific revolution did in the 17th Century – this shift precipitates a reassessment in what it means to be a human self.

In a nutshell, as the Cartesian and Newtonian visions of space came to form the basis of a new world picture, Western Europeans came to see them-selves in a radically different way

Understanding the relationship between space and self helps us make sense of the monumental transition entrained by modern science and can assist us in thinking through issues about what we might want from the new sciences now.

Mathematizing the World

When we look back at the scientific revolution, its outstanding feature is that people figured out how to begin to mathematize the world. Indeed, the foremost ‘scientific’ question throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was what features of the world might be amenable to mathematical treatment. Philosophically it was Descartes who articulated a coherent answer, setting the stage for the later empirical triumphs of Galileo and Newton, and all that came after.

According to Descartes, mathematics is applicable to the domain of matter in motion through space and time. So with math we can describe the trajectory of a canon-ball or cart or the motion of the planets and stars. Descartes coined the term res extensa to delineate the domain of mathematizable phenomena – the extended world consisting of things taking up physical space and changing in time.

But Descartes also understood that there had to be an intellective entity capable of engaging with the material world and discerning its mathematical qualities: “I think therefore I am,” he declared, placing the human self at the heart of his new worldview.

Clearly this I, this self, isn’t extended in space; it isn’t made of matter and doesn’t take up room so therefore can’t be part of the res extensa. Thus, Descartes said, there is a second domain of being, the res cogitans.

Being a Catholic, Descartes took the soul as vital part of the real, and for him the res cogitans accommodated both the Christian sense of a soul and what we today would call the ‘psyche,’ a secular concept of a self that feels love and senses pain, sees red and smells the scent of a rose. Critically, for him, the secular self was capable of rational thought. Here we have the self studied by modern neuroscience and psychology, the entity left over when you strip away the soul’s theological trappings. Shorn of any religious connotation, this modern self experiences percepts, which neuroscientists probe in labs and ‘philosophers of mind’ debate, the feelings of “what it is like” to see red or smell cinnamon

For Descartes, the res cogitans was as much a part of reality as the res extensa, and this bipartite schema was a foundation of his infamous dualism in which body and mind are separate and distinct aspects of the real.

How exactly the Cartesian body and mind interacted was a mystery, and a logical point on which he was challenged in his own time, and ever since. It is not my intention to defend this drastic ontological dualism, my purpose rather is to recognize the value of Descartes’ proposition of two spatial orders, two realms – or res’s – of being, one associated with matter and body, the other affiliated with mental and spiritual experience.

Descartes conception of the res extensa as the domain of matter in motion clarified for his peers what they should be focusing on in their desire to mathematize the world. Prior to this there had been attempts to quantify qualities such as sin and grace. Not the least of Descartes’s contribution to physics was his clear understanding that if the project was to succeed its scope would need to be narrowed and his articulation of how progress could be made by restricting mathematical study of the world to material things moving through physical space.

By the end of the 17th century, Newton had demonstrated the immense fruitfulness of this vision with a synthesis uniting the movement of bodies on Earth and the motions of the planets via a set of mathematical laws, the foremost being the law of gravity.

Infinite Space and the Erasure of Self

Yet Newton’s unification of the terrestrial and celestial domains raised an urgent theological issue. If we come to think of the extended realm (Desartes’s res extensa) as encompassing phenomena on Earth and the distant stars, then a question arises as to where this realm might end. Does it end at all?

In the early 18th century, Enlightenment thinkers began to answer affirmatively, reasoning that physical space is infinite. But if this is so, is there any room left for a ‘res cogitans’?

Once European scientists and philosophers embraced the idea of infinite physical space then Descartes res cogitans began to seem more and more like a fantasy. A new breed of rationalists rejected Cartesian dualism in favor of an ontological monism, now holding that the physical world is the totality of reality. With this perspective came the radical conclusion that thoughts, feelings, emotions and all the other paraphernalia of ‘self’ are merely secondary and ultimately insignificant byproducts of the ‘true’ reality of matter in motion.

In this way of seeing, Descartes’s ‘I’ – the human self – became a problem. At least for science. Not that anyone ceased to feel a sense of their own self – as if that were even possible. Rather, there was no way to talk about a self within the terms of science. Increasingly, proponents of science took to saying the self is an illusion, or even a delusion. A key component of this philosophical shift is that the in the age of physics, reality itself has come to be construed as the space of matter in motion. Now, if we want to claim something is real, we have to be able to pinpoint its co-ordinates in space and say “Ah it is here.”

Medieval Spatial Schemes

To give a sense of how monumental a move this was we can compare the new worldview with what preceded it in Western culture. Prior to the seventeenth century, Christians regarded themselves as bipartite beings, consisting of an entwined body and soul with each aspect again having its own spatial domain.

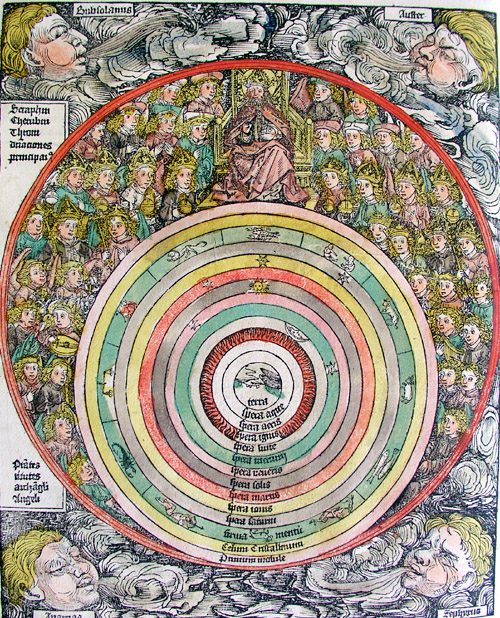

Physically speaking, medieval Europeans conceived of themselves as inhabitants of an Earth, placed at the center of a cosmos in which the sun, moon, planets and stars revolved around us on crystal spheres. This physical world was finite, so one could metaphorically imagine a realm beyond it – a place, or space, for the soul. In medieval imagery depictions of this cosmos show a small onion-like universe surrounded by the ‘ethereum Heaven’ or divine space of God.

-

Cosmos from The Nuremberg Chronicle

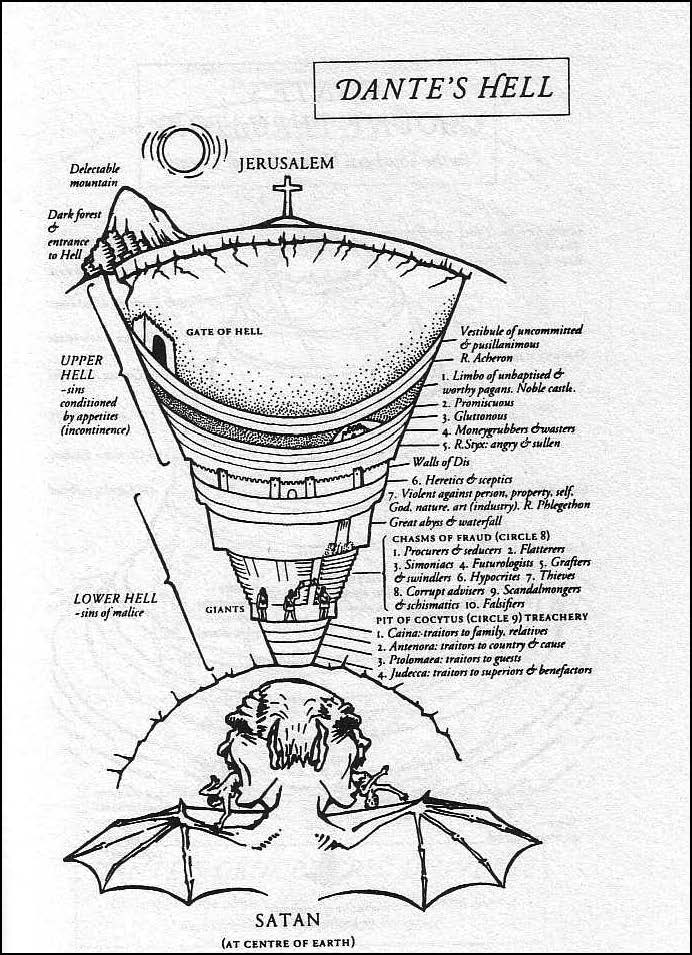

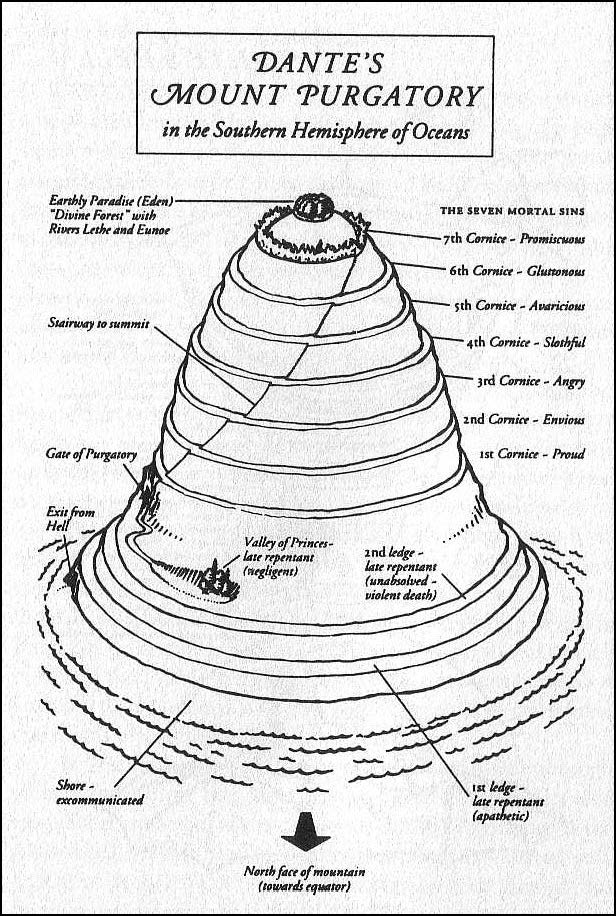

Just as physical space was layered in shells of increasing purity, so medieval spiritual space was organized as a hierarchy of grace. Moreover, it had its own topography, with the domains of Heaven, Hell and Purgatory so beautifully mapped out for us by Dante in The Divine Comedy. For medieval Christians this spiritual space was far more consequential than physical space, and thus more truly real, because it is in spiritual space that a person, or self, will spend the bulk of eternity.

-

Dante's Hell

-

Dante's Purgatory

The Divine Comedy can also be read as a pre-Freudian description of the psychological therapeutic process tracing a passage out of trauma – aligned here with a Christian conception of sin – through the healing of the self that can occur with careful introspection, ‘upwards’ towards a state of grace, represented by the numinous joy of Paradise. Additionally one could make the analogy that Divine Comedy is a pre-modern virtual world in which the hero is spiritually transformed through an epic journey encountering and overcoming his demons.

With the coming into being of the physicists’ world picture and the homogenization of space there was no longer any way to talk about such a transformation of self. Or to talk about a self at all. Descartes intuited what was a stake here, and I propose that one way of understanding his dualism is as an attempt to “save the phenomenon” of the soul while simultaneously developing a workable basis for mathematically-based science.

As long as people imagined the physical world was finite it was not such an imaginative stretch to believe there was something beyond it, however when physical space was re-conceived as infinite, such a perspective became much harder to cling to.

Does the Self Exist if We Can’t Pinpoint it in Space?

In discussions about the history of modern science and its impact on our thinking, much of the focus has been on the mechanistic perspective of nature and a consequent de-organicising of our conception of one another. My hypothesis is that an equally consequent, and perhaps more devastating move, was the infinitization of the physical realm.

What does it mean to say something ‘exists’ if we aren’t talking about a material thing with a defined position in geometrically describable space? Descartes, who gave us this vision with his invention of the Cartesian co-ordinate system – the very basis for modern physics – would have been horrified to see what his genius has wrought.

Seventeenth century theologians implicitly understood that the new mathematical science might threaten Christian worldviews, but it has not, I think, been sufficiently appreciated how the foundation of this science in a geometrical view of space presents such an ontological threat.

And whether or not one is spiritually inclined, the mathematical conception of space also presents a challenge for anyone who wants assert the reality of a self. John Locke foresaw this danger in the eighteenth century and suggested then it wasn’t stable for society to only have a science of the body. Locke believed people also needed a science of mind to describe and account for the phenomena of selfhood. Today we are seeing the coming into being of such a science – or sciences.

I believe this is a welcome development, for it seems to me Western society has been in kind of trauma since the physicalist perspective took hold. We are now desperately seeking a way out of its bind and the plethora of mind sciences today I read as a reaction, and hopefully as a corrective attempt, to give us back a language for talking about the self. I suspect we are just at the beginning of this journey and much of what is being said today in mind science will ultimately seem as simplistic as the first stabs at physics in the fourteenth century. But we are on the journey now, and that is a cause for celebration.

Margaret Wertheim is a science writer and author of books on the cultural history of physics, including The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace: A History of Space from Dante to the Internet. This essay extends ideas from that book and is based on a talk she gave at the International Forum on Consciousness, held at the BioPharmaceutical Technology Center Institute in Madison WI, September 2022.