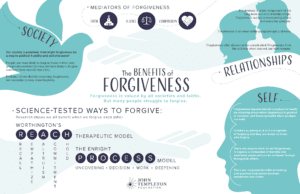

During the late 1990s, in the aftermath of the fall of Communism, Nelson Mandela’s election in South Africa, and an easing of the conflict in Northern Ireland, the world faced a new era in which former enemies tried to work with each other. Forgiveness took on new significance beyond religion, with which it had often been associated. The John Templeton Foundation issued a call for proposals that resulted in 20 funded grants, establishment of the non-profit organization, A Campaign for Forgiveness Research, which funded eight additional grants, and a total of almost $10 million put toward research on forgiveness. By 2005, this infusion of research money had moved the scientific study of forgiveness from 58 studies (1997) to over 1,100 published articles in 2005. Now, 15 years later, as we take stock of the benefits of forgiveness, we find that research has continued not just to grow, but to accelerate.

Benefits of Forgiveness: A Field Guide

The recent Handbook of Forgiveness, 2nd ed. (Routledge) has collected over 30 reviews or meta-analyses of subfields. Researchers have increased their attention to the context of transgressions, their aftermath, the behaviors and communications around transgressions, and the intertwined behaviors of offender and forgiver. Rather than emphasize only the experience of the forgiver, it pays attention to the entire set of experiences surrounding transgressions. That means that, although forgiveness of others is still the dominant research focus, researchers are also studying forgiveness of one’s self, intergroup forgiveness, and feeling as if one is forgiven by God.

Forgiving itself is also seen as more nuanced than it was 15 years ago. Rather than treating forgiveness as a generic process, many researchers are differentiating a decision to forgive from emotional forgiveness. A decision to forgive is primarily a decision to try to act differently toward the offender and, not seeking payback, treating the person as a valuable and valued person. Many people struggle with deciding to forgive, but once the decision is made, it is made—like turning on a light. On the other hand, emotional forgiveness is the (usually) gradual replacement of unforgiving emotions like resentment, bitterness, or anger with positive other-oriented emotions like empathy or compassion for the offender. Emotional forgiveness means that unforgiveness gradually lessens until neutrality is reached. Then, with a valuable relationship, one might continue to generate more positive emotions until a net positive feeling is restored.

Forgiving itself is also seen as more nuanced than it was 15 years ago. Rather than treating forgiveness as a generic process, many researchers are differentiating a decision to forgive from emotional forgiveness. A decision to forgive is primarily a decision to try to act differently toward the offender and, not seeking payback, treating the person as a valuable and valued person. Many people struggle with deciding to forgive, but once the decision is made, it is made—like turning on a light. On the other hand, emotional forgiveness is the (usually) gradual replacement of unforgiving emotions like resentment, bitterness, or anger with positive other-oriented emotions like empathy or compassion for the offender. Emotional forgiveness means that unforgiveness gradually lessens until neutrality is reached. Then, with a valuable relationship, one might continue to generate more positive emotions until a net positive feeling is restored.

One paradox that has been often noted is this. Most people highly value forgiveness. Religions advocate it. Talk-show hosts advise it. Yet, despite all this positive attention, most people struggle to forgive. The good news is that there are two well-established, research-supported programs to promote forgiveness—and there are many others that just have less research support, but the limited support for them is still positive. The two most supported methods are Robert Enright’s Process model and Everett Worthington’s REACH Forgiveness approach.

Want to read the full white paper on The Science of Forgiveness written by Dr. Everett L. Worthington?

Sign up to Access

Sign up today for free access to the full PDF and other exciting resources from the John Templeton Foundation.