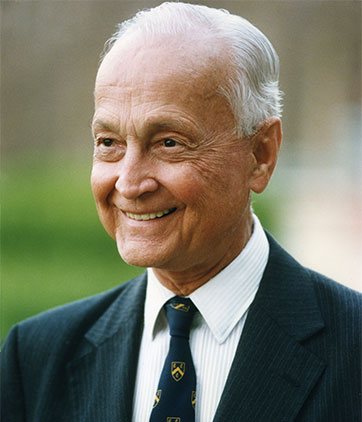

But John Templeton’s interests were never confined to the merely financial.

An unfailing optimist, a believer in progress, and a relentless questioner and contrarian, he devoted the second half of his long life to promoting the discovery of what he called “new spiritual information.” To his mind, this term encompassed progress in understanding not only matters usually considered religious but also the deepest realities of human nature and the physical world — that is, subjects best investigated by using the tools of modern science. Templeton was convinced that our knowledge of the universe was still very limited. His great hope was to encourage all of humanity to be more open-minded about the possible character of ultimate reality and the divine.

In 1972, he established the world’s largest annual award given to an individual, the Templeton Prize, which honors individuals whose exemplary achievements harness the power of the sciences to explore the deepest questions of the universe and humankind’s place and purpose within it. Its monetary value, currently £1,100,000, always exceeds that of the Nobel Prizes, which was Templeton’s way of underscoring his belief that advances in the spiritual domain are no less important than those in other areas of human endeavor.

Templeton also contributed a sizable amount of his assets to the John Templeton Foundation, which he established in 1987. That same year, he was created a Knight Bachelor by Queen Elizabeth II for his many philanthropic accomplishments. (In the late 1960s, he had moved to Nassau, the Bahamas, where he became a naturalized British citizen.)

Although Sir John was a Presbyterian elder and active in his denomination (also serving on the board of the American Bible Society), he espoused what he called a “humble approach” to theology. Declaring that relatively little is known about the divine through scripture and present-day theology, he predicted that “scientific revelations may be a gold mine for revitalizing religion in the 21st century.” To his mind,

“All of nature reveals something of the creator. And god is revealing himself more and more to human inquiry, not always through prophetic visions or scriptures but through the astonishingly productive research of modern scientists.

Sir John’s own theological views conformed to no orthodoxy, and he was eager to learn not just from science but from all of the world’s faith traditions.

As he once told an interviewer, “I grew up as a Presbyterian. Presbyterians thought the Methodists were wrong. Catholics thought all Protestants were wrong. The Jews thought the Christians were wrong. So, what I’m financing is humility. I want people to realize that you shouldn’t think you know it all.” He expected the John Templeton Foundation to stand apart from any consideration of dogma or personal religious belief and to seek out grantees who are “innovative, creative, enthusiastic, and open to competition and new ideas” in their approach.

Sir John’s progressive ideas on finance, spirituality, and science made him a distinctive voice in all these fields, but he never worried about being an iconoclast. “Rarely does a conservative become a hero of history,” he observed in his 1981 book, The Humble Approach, one of more than a dozen books he wrote or edited.